Talent, Conversing.

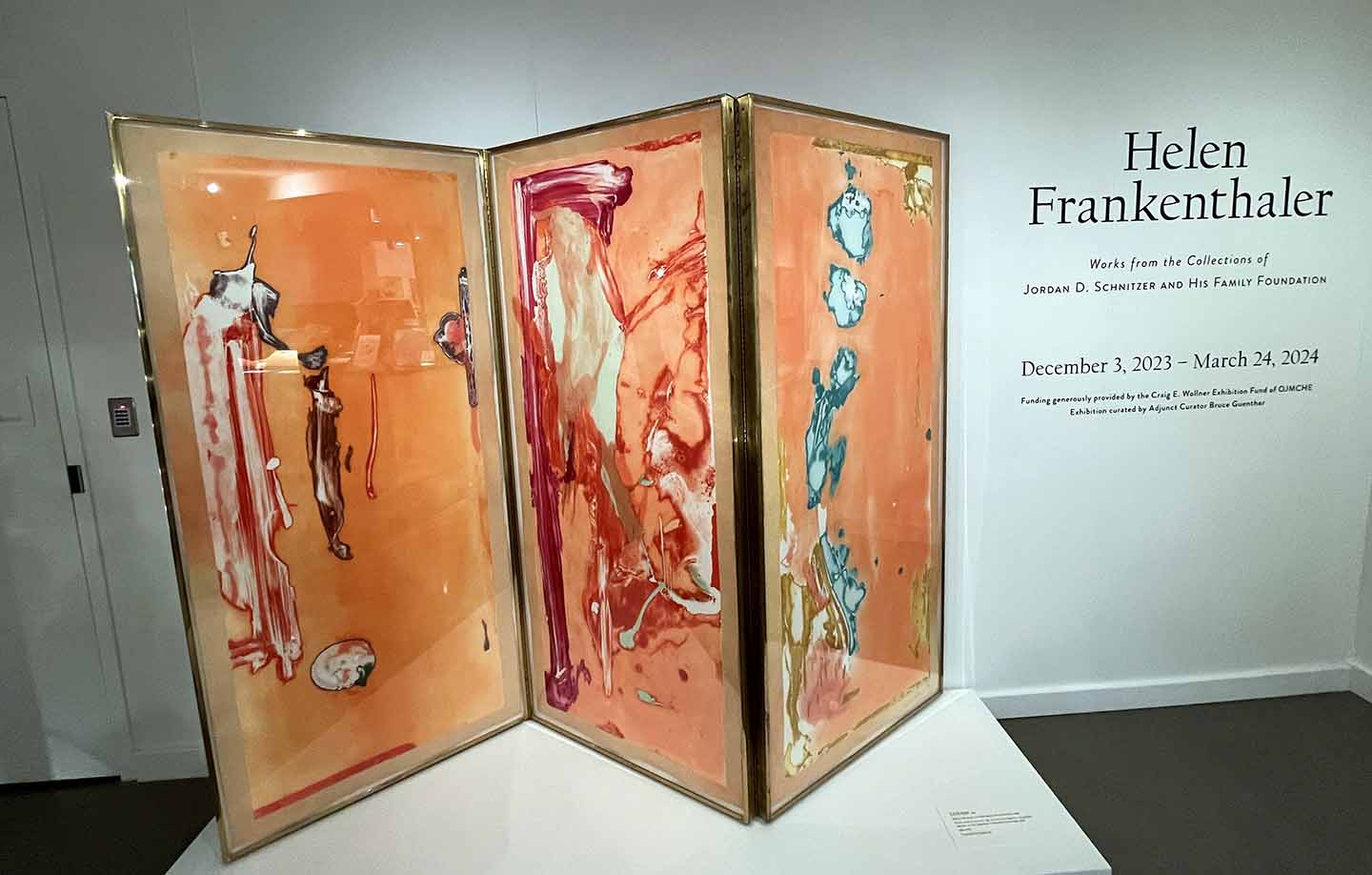

· "Dialogues: An emerging Artist Showcase" at the Patricia Reser Center for the Arts ·

May I suggest that when the weather permits you plan a visit to the Patricia Reser Center for the Arts in Beaverton? I predict you’ll find it worthwhile, telling by my own reaction when I was there on Wednesday.

Dialogues: An emerging Artist Showcase, shown in the gallery until February 17, 2024, is an exhibition with a sufficiently catch-all title that makes one wonder who is supposed to be talking to whom. The one voice that mattered, however, was heard – the art spoke to me. Or shall we say a lot of the art – so many varied voices: painting, sculpture, woodworking, installations, fiber arts, ceramics and photography – some loud, some whispering, some tongue in cheek and some refusing to tell a story unless you invested enough curiosity to find out.

In fact, dialogue is offered on multiple levels – the artists, all still in training, self-taught, or recently graduated, reach out to the viewer in direct appeals to converse. Or they confer with imaginary representations of the past, unraveling narratives that cloaked something else. Or they are settling scores with departed lovers, or yell back at a world that is intolerably judgmental, or deliver simple, but insistent monologues. Then there are the conversations between those looking at the art and offering different takes. Or, if you’re lucky, you get to listen to the curator, Karen de Benedetti, explain some of the works that benefit from background information. Much talk in this gallery!

The Gallery at the Patricia Reser Center for the Arts

The level of talent and expertise was as varied as the voices on offer, and that is a good thing. For me, one of the outstanding services The Reser Gallery provides for the community is the approachability of art for populations that are not necessarily familiar with it or are shy to reveal their own lack of knowledge, putting “art” on a pedestal. Showing art by young people who are still in the process of finding their voice, or the facility with the tools to express their ideas, is so very encouraging for the rest of us who are drawn to it but might feel inadequate. It creates engagement and might spark artistic explorations for those who can observe here that work evolves and improves over time, far from perfect in early stages of a career.

Noelle Herceg Jellashells Installation

That said, there were creative ideas all around the building, and some serious beauty to be had, with or without narratives. I will not be able to talk about them all; after all you should visit and see for yourselves! Instead I chose a few of the story tellers whose stories moved me, and a few artists who helped me to stop thinking or forever running my brain, by presenting work that simply enticed with visual beauty, feeding my eyes and soul instead.

Jessica Joner Of What Was

Upstairs a table surrounded by chairs awaits you, quite literally inviting people to sit down and talk, with many following the invite during the opening night, by all reports. Everything on the table is made or created by the artist, Jessica Joner, who embroiders surfaces with encouraging messages, and offers pottery for a multiple course meal. I spontaneously use the word inviting, but that is really how her work feels on second thought: it invites you to be with her, her ideas, her audience, an act of sharing, opening dialogue in the community.

Jessica Joner Respite (left) Ceaseless (right)

Downstairs my eyes were drawn into a large, multiple-part installation that on first glimpse seems to tell one story, and upon closer inspection hides a second, underlying, much darker narrative. Katherine Curry‘s surface depictions, with computer-assisted cuts of wooden circles into the most intricate doilies next to a video of the slow unraveling of a delicately crocheted doily by the artists hands, tell of family traditions of specialized handiwork, patterns handed down from generation to generation. Behind the beauty and the shadow play of the wooden models lurks something uglier, seemingly making its way through the generations as well, with family represented in a large photograph behind the lacy screen, trying to put a conventional smile on the face of harshness, if not intimations of violence.

Katherine Curry A Nuclear Family Details below

A bit further into the room, handmade soaps covering photographs of family members echo the theme of a film of civility cloaking the tension underneath.

Jessica Joner Wash your Mouth out Again and Again and Again

One returns, if these are the interpretations that formed, almost with relief to the video where the unraveling of a pattern now takes on a restorative tone: there is an end of the line, the string freed, and the path to something new is open.

There are other stories to be found in the gallery: the miniature perfection of a dream meal envisioned by someone with allergies suffering a restrictive diet (Leah Yao well aware of the consequences of junk food down to the grave.)

Leah Yao Mini Memento Mori Details below

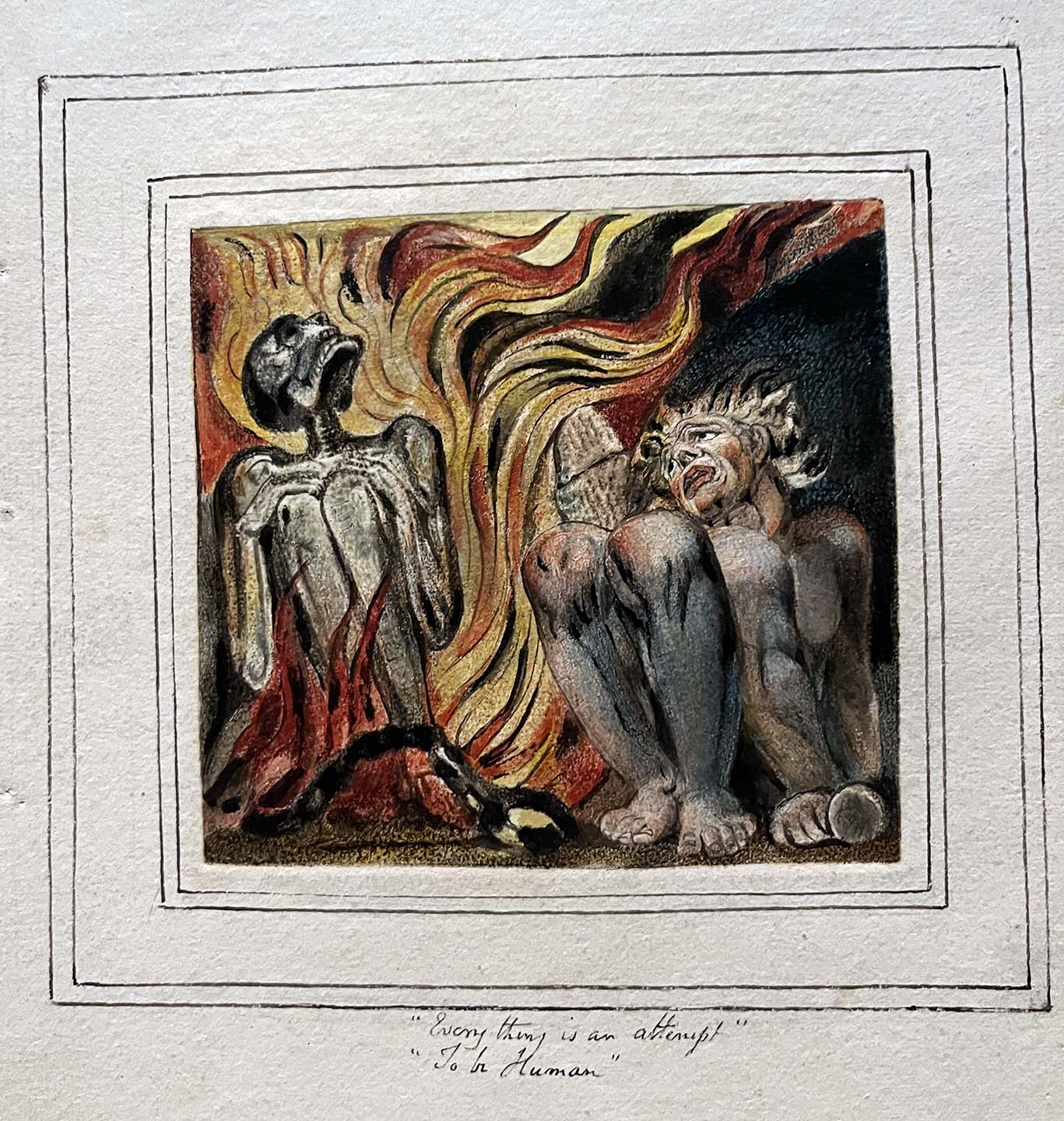

A letter written after having been abandoned, Eliza Williams‘ incantations feeling like an attempt at self hypnosis to get over the spell cast by the lover. You’ll see for yourself, if you have a chance to visit, how many variations there are of engaging in one or another form of speaking out.

Eliza Williams I used to know you Details below

Quieter work, or shall we say work absent a storyline, was also well represented. There were ceramic containers by Kelsey Davis Hamilton, carefully placed on chosen fabric echoed in some form or another in her voluptuous sculptures that reminded me of tropical succulents, their lack of restraint juxtaposed with these constrained patterns from tartans to the dot alignments familiar from eastern European stoneware.

Kelsey Davis

Kelsey Davis Her House of Laughter

There were Tanner Lind‘s works on paper, radiating joy, the smaller ones more successful than the larger ones. The former were not shy to allow background breathing room to provide a stage for the perceived movement of the affixed figures. It is terrific work, reminiscent of Alexander Calder or Joan Miró if you blink, but in no way derivative. Leaving space empty when there is a lot of space to fill is definitely difficult – but Lind’s unerring sense of geometry and color should propel him towards solutions.

Tanner Lind Microzone 1 (left) and Microzone 2 (right) (perfectly placed above the recycling containers that lend themselves to a Gesamtkunstwerk….)

Tanner Lind Microzone 3 Details

I was absolutely smitten by an installation of organic shapes that hung in the window on the ground floor. Noelle Herceg creates these ephemeral shapes from gelatin, a material that makes them prone to fading, breaking, given that Jell-O skins are not exactly meant to last. I first thought they were made out of glass. Learning that they were not, added a memento mori quality to the work that enhanced the appreciation. Herceg’s website (link above) explains both process and underlying thoughts about her approach in better detail, both concerned with memory of a past and a loss thereof.

Noelle Herceg Jellashells

A few months ago I had explored another exhibit with organic shapes hanging from above, albeit huge ones. Woshaa’axre Yaang’aro (Looking Back) by Mercedes Dorame is an installation at the Getty Center in L.A., conjuring the views of ocean coastlines of the Tongva People, with the suspended sculptures representing abalones – a culturally important mollusk for the Native peoples. This artist, too, relates work to memory and the constructs built around what gets handed down. I found the size overwhelming, though, and the opaque pastels too saturated.

Mercedes Dorame Woshaa’axre Yaang’aro (Looking Back) at the Getty Center

Herceg’s work, in contrast has a gentleness to it, a cautiousness almost, as if there’s fragility all around us, one sharp look potentially shattering skins. Really hard to convey, and perhaps just my personal echoing of the theme, but the installation is worth exploring, something digs deep.

Noelle Herceg Jellashells

Last but not least let’s make some room for talking with your hands… or at least one prominent finger extended to all those engaged in fat shaming – here’s to holding your ground! The zest for life depicted in this painting -oh grant me just a small percent of that!

I expect we’ll see many of these young artists more prominently in the years to come, if we are lucky to be around. The Reser show certainly raised hopes for that.

Rae Sheridan Vickie

In keeping with the theme, music today is a dialogue between two instruments, a terrifically re-arranged Rite of Spring for piano and marimba.