If you asked me if I prefer exhibitions that feature a single artist or those that display the work of many different ones, I’d have a hard time deciding. I always find myself drawn to retrospectives of a particular artist, because they allow me to learn how someone develops, how they are open to change or impress with continuity of a chosen theme, and how life’s experience(s) can shape the evolution of creativity and skill.

On the other hand, seeing the works of many different artists riff off each other, or provide comparison basis for relative judgements, allow an assessment of the current state of the art and often help me to understand my own reaction to art better, my own taste, if you will.

Art at the Cave gallery rooms

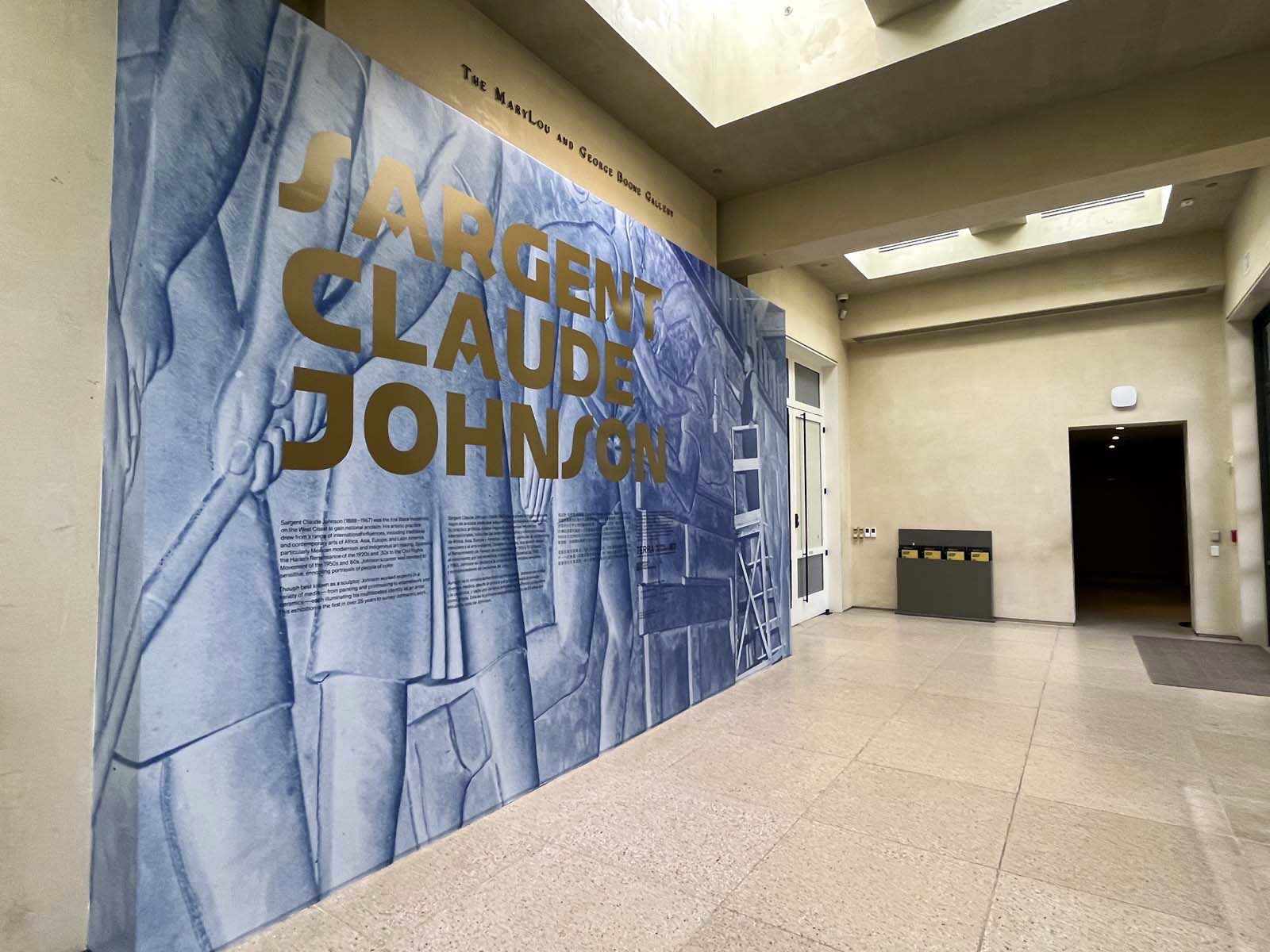

Luckily, today we don’t have to decide between the two approaches: I’ll just present both. I managed to see a riveting retrospective of Sargent Claude Johnson‘s work at The Huntington Library in Pasadena, CA, still up until mid-May. I also visited Shapes that Speak, work by multiple members of The Pacific Northwest Sculptors Group (PNWS) shown during the month of April at Art at the Cave in Vancouver, WA. (I chanced on it, just before closing. Some of the work is truly interesting and you might enjoy looking at the portfolios. Here is a list of the PNWS members with their websites for your perusal.)

Tony Furtado Hiro the Hare

Shapes that Speak is such a catch-all title, but I would be hard pressed myself to come up with something more specific for a group exhibition that is not curated around a particular topic. If these sculptures speak, then surely in different languages, with different degrees of precision, loudness and pitch. Structure varies, just as texture and modes of expression. I would not call it a cacophony, but the Tower of Babel did come to mind.

Tony Furtado Husk

In a way that is the one drawback, compared to all the advantages conveyed by being a member of an artist collective – in this case Pacific Northwest Sculptors, long a treasure for the region – that provides mutual support and exchanges resources and ideas, educates and connects. Group exhibitions of member work can so easily become byzantine, with the viewers having to make their way through a seemingly haphazard collection, trying not to be distracted by too many voices at once, to stick with the metaphor. That said, whoever hung this show did admirable work in grouping exhibits otherwise all over the map.

Left to Right: Laurie Vail Dancer – Bill Leigh Flight – Laurie Vail Kingfisher

Left to Right: Jeremy Kester A Drop in the Ocean – LB Buchan Elysia – Todd Biernacki Homage (c’est un Magritte) – LB Buchan Propeller 2

Note that I believe both to be true: the advantages of artist groups like these far outweigh the disadvantages, and exhibitions could be showing off the strength of each artist if curated around a shared theme, or some underlying principle. Simply putting up recent or favorite displays does a disservice to much of the work that would otherwise shine.

Sherry Wagner Mary

Leslie Crist Portrait (photographed from different angles)

Here are some more examples of the diversity I encountered, in no particular order or preference.

Susan Jones Laminar Flow

Anne Baxter Solar Flare

Sherry Wagner Chip

If the work of the Pacific Northwest artists tell many different stories, Sargent Claude Johnson‘s retrospective at the Huntington is devoted to a main focus: the dignity and beauty of the Black subject in an era that still legalized racial discrimination. It is long overdue to see work from a master, namely a quarter century since his work was surveyed at SF MOMA, and one wonders why an artist who was so prominent during his lifetime has disappeared into the recesses of cultural memory.

The Black modernist (1887 – 1967), often associated with the Harlem Renaissance, lived on the West Coast for most of his lifetime and worked primarily as a sculptor in contrast to his painting East Coast associates, which might explain why he fell through the cracks when this movement experienced renewed interest by contemporary art critics. (In this context it might be or interest to visit a wide reaching exhibition on the Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism that just now opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC.)

Negro Woman (1933)

Johnson was born to a father of Swedish ancestry and a mother who was part Cherokee and part African American. While his brothers and sisters chose to be recognized as Native Americans or Caucasians, Sargent decided to live his life as a Black. Some of his work, like this portrait, focussed on the duality of his racial background. In his own words, “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others… One ever feels his Two-ness, – an American, a Negroe; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body.”

Self Portrait (1950s)

This is about the most political statement by him that I could find. In general, the artist did not engage in propagandistic art, whether in his murals or in his work for collectors, and was wholly opposed to the social realism found in the work of other Black artists, like Elizabeth Catlett, Jacob Lawrence, and Charles White. He shared the somewhat apolitical aesthetic stance of a man he admired : Alain LeRoy Locke, the so-called father of the Harlem Renaissance, whose “New Negro” philosophy assumed that “a vibrant race tradition in art will contribute to American art and, in turn, this achievement will help bring about social equality.” (Ref.)

Langston Hughes, a former protégé of Locke’s, considered the Harlem Renaissance movement a failure because it was motivated by a fantasy that the race problem could be solved through art. He accurately wondered whether the contributions of an elite group of black intellectuals to American culture would bring about social change for the masses of African Americans.

Johnson drew from Southern Black folk-culture and African art as sources of inspiration, but also included aspects of Asian-Pacific art. Many elements of pre-Columbian or contemporary Mexican art can be found in his sculptures and friezes. He experimented with various modes, sculpture predominantly, but also painting and prints. A range of materials, wood, paper, metal, enamel, terracotta and more, can be found in his work.

Singing Saints (1940)

Dorothy C. (1938)

Johnson is probably best known for his sculptures, many of whom depict Black women, often with children inseparably attached, a valuable reminder that family separation is not just a thing of a slavery past. Immigrant families, separated at the border during the last eight years, are still not reunited, often due to (coincidental?) administrative omissions of identifiable characteristics that would allow tracing.

Standing Woman (1934)

Forever Free (1933)

Mother and Child (1932)

Some of Johnsons’ children’s busts received awards. Minor quibble for an exhibition that otherwise does a fabulous job in both placing and signage of work: why elevate the one non-Black head to central and elevated position? The little Asian girl was a playmate of Johnson’s children, but it feels weird that she is surrounded by the Black kids.

Clockwise from upper left: Head of a boy (1930) – Elizabeth Gee (1927) – Chester (1931) – Head of a Boy (1928) – Esther (1929)

Johnson worked all his life in side jobs to sustain his artistic practice. Money was tight, which had sorrowful consequences for his wife whose mental health declined and who spent the rest of her life in a mental institution. (The Huntington is truly helpful in providing much information of aspects related to the artist but not necessarily central to the art in its catalogue.)

Even though Johnson was picked for major commissions, including a 185-foot-long frieze for a San Francisco high school that displays an array of athletes, things never got easy. Other public artworks for the Depression-era Works Progress Administration included work for the California School for the Blind in Berkeley.

The following architectural installations were all made for the CALIFORNIA SCHOOL FOR THE BLIND starting in 1933. There are window lunettes and a stage proscenium. The pieces were dispersed and now belong to the Huntington, The California School for the Blind, the African American Museum at Oakland and UC Berkeley – here reunited for the first time. You are invited to explore via touch!

Here is video that describes the work.

Below is a video screenshot and sketches for San Francisco’s George Washington Highschool Athletics Mural from 1941. Here is a full video.

Johnson’s life did not have a happy ending. He struggled with the ravages of alcoholism and died in 1967 in a residential hotel in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district, a somewhat rough neighborhood. His legacy should serve as an inspiration: he told the story of the dignity of people who were ignored at best, despised and discriminated against at worst, art created during a time where this was an act of defiance as well as an expression of hope against hope to help change perceptions.

Alas, this particular story is still ongoing.

Standing Woman (1934)

Here is music from the Harlem Renaissance. Lift every voice.

Sargent Claude Johnson

Feb. 17–May 20, 2024

The Huntington – Library, Museum, Botanical Garden

1151 Oxford Road

San Marino, CA 91108