What to do with the past?

· Stitching Stories at Art at the Cave Gallery in Vancouver, WA. ·

“If nostalgia as a political motivation is most frequently associated with Fascism, there is no reason why a nostalgia conscious of itself, a lucid and remorseless dissatisfaction with the present on the grounds of some remembered plentitude, cannot furnish as adequate a revolutionary stimulus as any other: the example of [Walter] Benjamin is there to prove it.” – Fredric Jameson, “Walter Benjamin; Or, Nostalgia,” Marxism and Form, 1971

Bonuspoints for a gallery that makes you wonder before you even set foot into the building! At least that’s how I reacted when I arrived in Vancouver to meet with one of the artists currently exhibiting at Art at the Cave and was greeted by a sign sporting multiple promises – some of which were indeed kept by the work shown inside.

Stitching Stories features multiple artists, loosely connected by work using stitching and weaving, their work triggering immediate associations of past, present and future for me, the flow of time signaling change.

Sharon Svec, part of the gallery team and one of the exhibiting artists.

Sam Yamauchi‘s A Messy Book of Mistaken Identity symbolizes the hazards of both, a search for and communication of identity to others. The stitched collages unfold in the here and now, boldly describing a process affected by variables all too familiar for many of us, rightly questioning if there is a permanent, identifiable self to be found.

Sam Yamauchi A Messy Book of Mistaken Identity

Sharon Svec‘s The Eyes Have It is an enchanting set of three eye-shaped, sculptural mobiles intricately woven from roots of ivy, some starting to sprout leaves in the warmth of the cavernous room. The robust material (have you ever tried to get rid of ivy roots in your garden?) takes on a more filigree appearance when laced together, light suffusing in both directions. The combination of light and eyes, three of them no less, triggered amused associations of clairvoyance, the third eye predicting the future – and the evanescence of such attempts. The German word for clairvoyance is Hellsehen, seeing the light. I have always believed that that is a much more applicable description of our take on the past when we come to inspect it, rather than a grasp on the future. But what do I know.

Sharon Svec The Eyes Have it.

***

The past, as it turns out, is what I came for, drawn by two bodies of work by Ruth Ross, Yiddish and The Doll Dialogues, respectively. More precisely, I was interested in how the artist approaches the past. Honoring the past in an attempt to defy impermanence, holding on to it to prevent its loss, turning nostalgic to retrieve remembered affect? Her frequent use of discarded fabrics, beyond their prime and found in thrift store bins or yard sales, often applied back to front, had a material feel of things dragged up, preserved to last. Yet with all her work, things go far deeper than that.

Yiddish is, in some ways, the perfect vehicle for considerations of preservation and loss, not just in the intimate sphere of what’s spoken in one’s family to which Ross refers. The language itself is about 1000 years old, spoken by Ashkenazi Jews, with the name Yiddish itself meaning Jewish. It had other names as well, Taytsh (German), Yidish-taytsh (Jewish-German), Loshn-ashkenaz (the Ashkenazi tongue), and Zhargon (jargon,) but Yiddish remained the standard reference since the 19th century. Before the Holocaust there were over 10 million people in the world speaking Yiddish, a number that was, in addition to the murder of 6 million Jews, further diminished by processes of acculturation and assimilation in America and the former Soviet Union, and by repression of Yiddish and acculturation to Hebrew in Israel. (Ref.)

Ruth Ross Balabusta (Housewife) Details below

Feh signals contempt…

The language itself went through many permutations but generally allowed people who were living in the diaspora to have a shared means of communication. It consists of multiple elements from other languages, Romance in origin, German and Rabbinical Hebrew among them. Each new region where Jews settled after having been driven out from other countries, developed its own vernacular, creating hybrid words, just as we see in so many other languages. The different dialects spoken throughout different European regions were interspersed in American Yiddish, when the immigrants arrived, and standard Yiddish now contains many English words as well.

It has been a two-way street, clearly. Many of the words Ross chose, stitched with wit, subtle hints, allusions to childhood memories and an attentive eye for type-face design, are part of our own English vocabulary, used frequently without knowing their origins. That is even more true for the German speaker. I certainly grew up with everyday words that turned out to be Yiddish when I thought they were German, adjusted in their spelling. In fact there are over 1000 of them, with about 30 in heavy rotation, Schlamassel (Shlimazl – bad fortune or things gone wrong,) malochen (physical labor, from Maloche – work,) Ganove (Gannew in Yiddish, a petty criminal) or Techtel-Mechtel (a fling, derived from the yiddish word Tachti, which means secret) among them.

Ruth Ross Schlemiel/Schlimazel (A Schlemiel is the person who spills the soup and a Schlimazel is the person it lands on…)

Ruth Ross Nu? (Whassup)

Last year I reviewed Ross’ extraordinary series, Red Scare, about being Jewish, politically active and under threat during the McCarthy era. It had a strong political voice, something that is less obvious but still notable in the current exhibition. To draw attention to a language that has long served to identify yourself as a target for anti-Semitism is the opposite to what so many Jews, particularly of the artist’s parent’s generation, were told to do in order to assimilate. There are whole books written about the slogan Dress British, Think Yiddish that encouraged Jews to blend in, in order to be admitted to institutions of higher learning, in particular the Ivy Leagues. Keep your identity inside, think, don’t speak Yiddish. Variations on this can be found as recent as a decade ago, when the originally Jewish sartorial empire, Saks Fifth Avenue, teamed up with a company that made adjustable stays for men’s shirt collars, imprinted with Yiddish words, functionally hidden from view in their little collar slots. The special collection’s name? “Think Yiddish, Dress British.”

Ruth Ross Schmatta (A rag, or piece of clothing)

Ruth Ross Nudnik (A pestering or irritating person. As the artist related, her Papa used to call her that in exasperation when she disturbed his peace.)

Here is work that draws attention to identity, created during a time when people are physically attacked on the street just for speaking Hebrew, two months ago in Berlin. A time when, closer to home, Marjorie Taylor Green suspected that California wildfires were started by Jewish space lasers, and exhibited during a time where Gaza has become a killing field. Plainly there are people in the world who will suspect us, dislike us and maybe despise us because we are Jewish. This point is certainly amplified by many people’s reactions to the horrors unleashed upon civilians in the Middle East. And therefore, unsurprisingly, there is some apprehension associated with letting people know that you are Jewish, and a Yiddish speaker. In addition to concern about vulnerability, many Jews feel some sense of shame or rage about what the government of Israel is pursuing in reaction to the horrifying attack by Hamas, and know we will be called anti-semitic if we voice our anti-Zionism, call for a cease fire or add our voices to the chorus of Jewish voices for Peace. To embrace an essential part of your identity then, in public, is a political act.

Ruth Ross The Royal OY and Gevalt

***

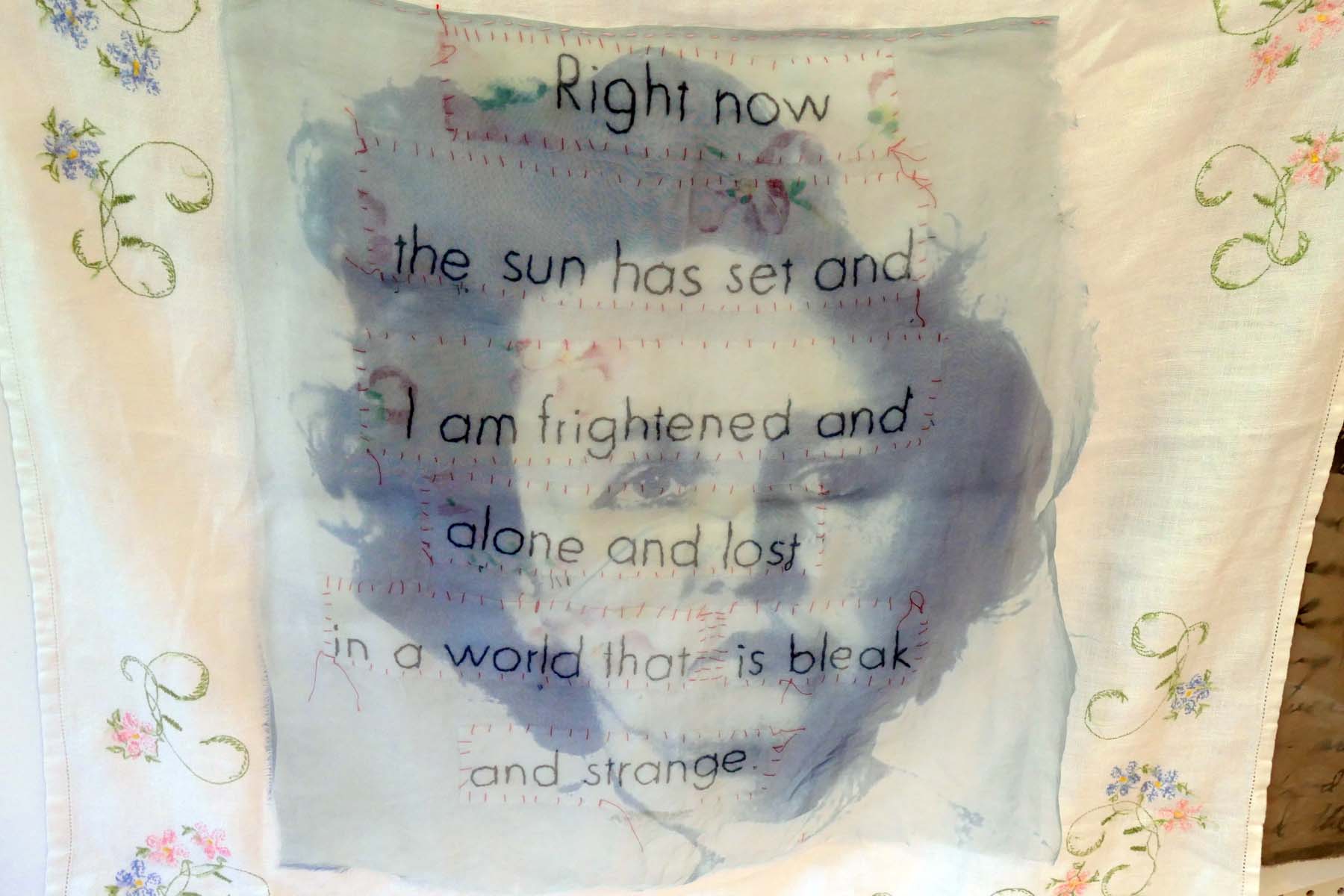

Ross’ second body of work references personal history as well, her life-long relationship with her dolls. Where Yiddish is explicit, straight forward, easily deciphered work, the Doll Dialogues appeared to me to be the opposite. Gauzy layers, combining laser prints on silk, gel prints on silk organza, and lace appliqués with occasional embroidery make for mysterious tableaux each with an obscured doll at its center.

If you are so inclined, they invite psychoanalytical interpretations of childhood memories, symbolized by the dolls, long veiled and inaccessible. After all, here is what Freud wrote:

. . . In the so-called earliest childhood memories we possess not the genuine memory-trace but a later revision of it, a revision which may have been subjected to the influence of a variety of later psychological forces. Thus the “childhood memories” of individuals come in general to acquire the significance of “screen memories”and in doing so offer a remarkable analogy with the childhood memories that a nation preserves in its store of legends and myths.

—Sigmund Freud, “Childhood Memories and Screen Memories,” 1901

If you are like me, you will rather think about the symbolic value that dolls take on in their respective contemporary settings. They might not always be as explicit and creepy as the ones used by Hans Bellmer, who withdrew into the privacy of his obsessions in response to the Nazi’s imperatives about healthy rather than “degenerative” art. They might not be as culturally appropriated as Max Ernst‘s works derived from his collection of Katsina dolls of Hopi origin. But dolls do have a role within a political context, just as they had symbolic value since their inception so many thousands of years ago, first in religious settings, then as status symbols for the aristocracy and eventually as a plaything intended to shape little girls into their roles of care takers and mothers in the context of the nuclear family.

Ruth Ross On the Bus

Ross’ depiction of her dolls is shrouded in more ways than the visual one. Their titles refer to occasions down the memory lane of the artist, rather than serving as explanatory pointers. Their appearance is at times surreal, at times androgynous, hazy and dark. Lace and silk notwithstanding, there is no sense of an exaggerated female presence, a dress-up tool or emphasis on beauty. No hint of happy, innocent tea parties. These collages are blissfully free of nostalgia, even when tied to personal experiences of the doll’s owner.

Why do I celebrate that, you wonder? What’s wrong with a bit of nostalgia?

We live in an era where nostalgia for the traditional role of women, playing house, being subservient, acting doll-like, enjoying the kitchen (Senator Katie Britt, we see you!) is making an organized come-back. It is signaled to a receptive public, yearning for a “traditional past” by ever so many flags, a baby voice appropriate for doll play among them. It has, however, nothing to do with how the dictionary defines nostalgia: “a sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past, typically for a period or place with happy personal associations.”

Rather, during (aspiring) fascistic eras it becomes a political tool: Reactionary nostalgia creates a cultural identity by mystifying past and present. The myths of racial superiority and the claimed heritage of a superior religion or immutable gender hierarchy promises succor to those who are feeling deprived and demoted in their present-day existence. That was true for historical periods in the last century, be it in Germany or Italy, or Spain. It is true now for Russian claims of rights to land and resources, and we see it in our own country when we look at the justifications for political movements, Supreme Court sanctioned and enabled, that try to turn the clock back and remove rights extended to those who did not originally occupy the top of a hierarchical ladder (for that matter, who still don’t…)

Ruth Ross She laid her Baby at my Feet detail below

Rather than engaging in nostalgia, we should acknowledge that the past cannot be completely retrieved, and should inform the present only in so far as it allows us to discern what parts of the past should not be repeated. Clinging to conceptions of power that should be assigned to certain people in perpetuity, at the expense of others, is unjustifiable. So is clinging to ideas of permanent victimhood, used as justification by people to become perpetrators regardless of the horrors that they will unleash.

Ruth Ross Love this Doll to Death

The dolls in this exhibition are ambivalent enough that they invite associations to both, object and subject, good and evil. They are a welcome reminder that we need to lift the veil that obscures some version of truth, a veil fashioned out of our clinging to an imagined past, blocking our vision of a more equitable future.

STITCHING STORIES

Ruth Ross & Sam Yamauchi

MARCH 2024: Artist Talk from 1-2 pm on Saturday March 16; a reading by Ruth Ross’ guest poet Leanne Grabel on March 23 at 3 pm.

ART AT THE CAVE, 108 EAST EVERGREEN BOULEVARD, VANCOUVER, WA, 98660,

Music today, how could I not, is the mechanical doll’s aria from Offenbach’s Hoffman’s Erzählungen.