This week was mostly devoted to how to find things that are lost or stolen: archeological treasures, land, art. The academic discussion around textual archeology, learning from past texts, literary or otherwise, eventually had me think about maps.

Maps, you know, those paper things that half of us can read and half of us cannot, that pointed the way to our destinations before the arrival of talking machines that tell you how to proceed – and then reroute. Maps, now seriously, that were supposed to adhere to “the empiricist paradigm of cartography”—that “cartography’s only ethic was to be accurate, precise, and complete.”

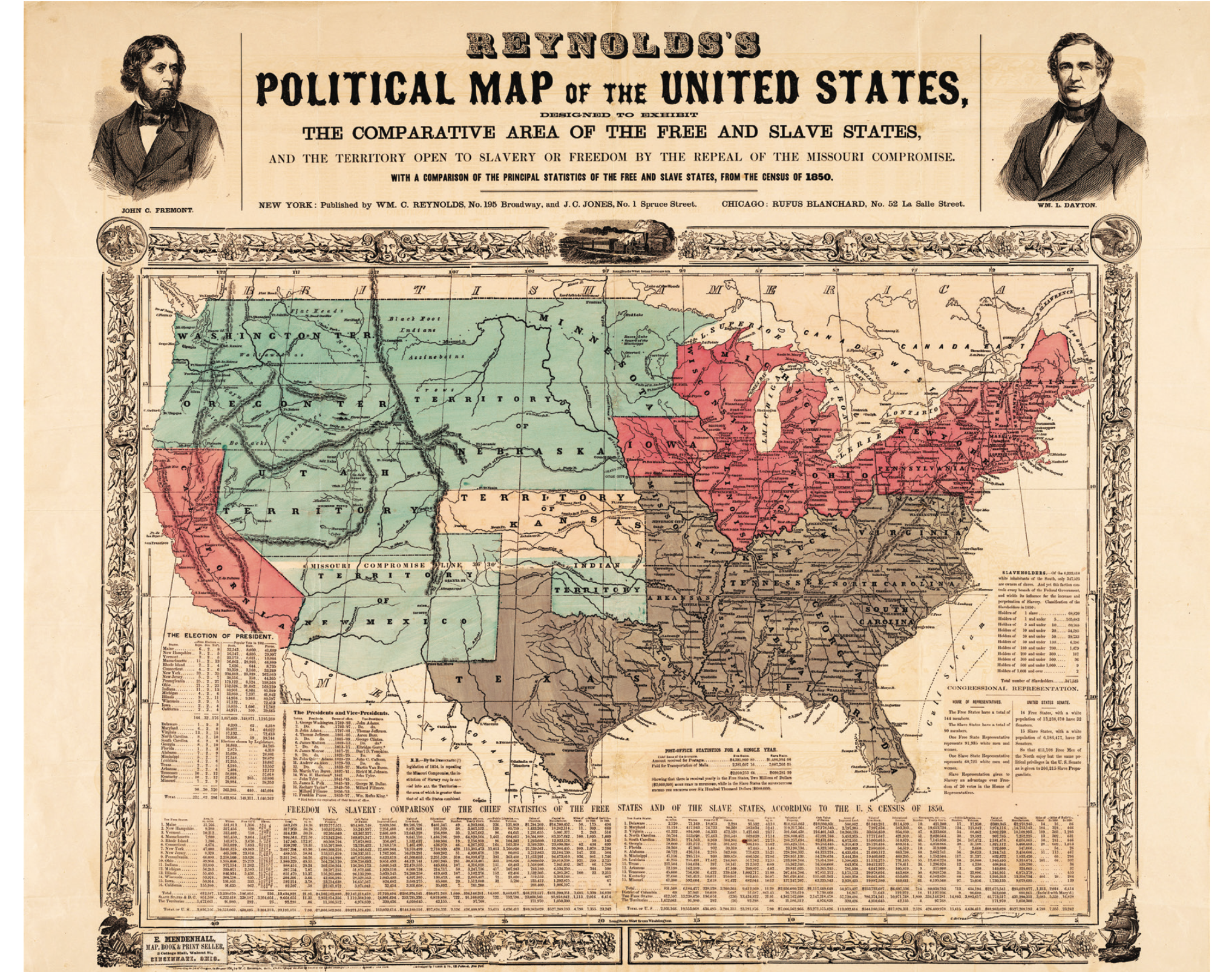

Since the 1970s, this view has been strongly challenged, and there are many enlightening efforts to reveal what maps are often really all about – persuasion to accept a particular view of the world, and not just geographically. For example, in 1992 the Cooper-Hewitt Museum in NYC put on a show about “all maps –whether rare or familiar, new or old, Western or non-Western — are more than simply guides to help you find your way. Like advertisements and other forms of graphic design,maps express particular viewpoints in support of specific interests. Depending on their function and purpose, all maps present information selectively, shaping our view of the world and our place in it.”

One of the best collections of these type of maps can be found at Cornell, see the link attached above. A great discussion of what is on offer – and what is at stake – can be found here:https://persuasivemaps.library.cornell.edu/sites/default/files/PJM%20Persuasive%20Cartography%20Portolan%20%23100%20Winter%202017.pdf

The author argues that persuasive cartography is as old as mapping itself. Its scope ranges from religion, imperial geopolitics (think colonialism), slavery, British international politics, social and protest movements to, of course war. It was made explicit in the 1920s (and later taken on in force by the Nazis) when in reaction to the shameful defeat in WW I German cartographers decided to go for the “Suggestive Map,” cartographic propaganda which they thought had given the British a strategic advantage.

“The goal of suggestive mapping was to achieve political objectives (while avoiding lies, which could be easily exposed) by appealing to emotions and rigorously excluding anything that didn’t support the desired message. Its maps were intended specifically to engage support from the general population, and they were often “shamelessly explicit. The movement produced “striking” results: by the early 1930s “there was a ‘virtual flood’ of suggestive maps in Germany; entire atlases were devoted to them, and they appeared in “every public lecture, every newspaper, and in countless books.”

In the 1970s Brian Harley and many other progressive historians pointed to the fact that persuasive cartography was not restricted to a particular nation or political movement. “Social purposes between the lines” were typically the goals of the authoritarian elite, who used maps to legitimate their power and manipulate the weak.” If you look closely at the maps I am posting today instead of photographs, you’ll get the point.

A great overview of myths, lies and blunders on maps can also be found here:

https://hyperallergic.com/348907/the-phantom-atlas/….

and that is before we even get to maps of fantasy worlds…..

Music today is about a traveling man who could not have been saved by the best maps in the world: The flying Dutchman. If you are not up to listening to 3 hours of Wagner, there is a hilarious 3 minute version ….

The real thing is attached here. As typical for Wagner (reminded by the spoof above): the men need redemption, the women do the sacrificing. And that pattern is pretty well mapped out…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b9b97PZUykE

And here is the last poem one of my favorite poets ever worked on:

MAP

Wisława Szymborska

Flat as the table

it’s placed on.

Nothing moves beneath it

and it seeks no outlet.

Above—my human breath

creates no stirring air

and leaves its total surface

undisturbed.

Its plains, valleys are always green,

uplands, mountains are yellow and brown,

while seas, oceans remain a kindly blue

beside the tattered shores.

Everything here is small, near, accessible.

I can press volcanoes with my fingertip,

stroke the poles without thick mittens,

I can with a single glance

encompass every desert

with the river lying just beside it.

A few trees stand for ancient forests,

you couldn’t lose your way among them.

In the east and west,

above and below the equator—

quiet like pins dropping,

and in every black pinprick

people keep on living.

Mass graves and sudden ruins

are out of the picture.

Nations’ borders are barely visible

as if they wavered—to be or not.

I like maps, because they lie.

Because they give no access to the vicious truth.

Because great-heartedly, good-naturedly

they spread before me a world

not of this world.

_

Translated, from the Polish, by Clare Cavanagh

NewYorker April, 14th, 2014

Kimberly Marlowe Hartnett

One of your best essays and…those maps! Wow. The poem at the end is utter truth, and pretty much perfect for our times.