WE LIVE IN AN ERA where the necessity to decarbonize the world’s energy has become quite clear, even if the oil and gas-based industries fight tooth and nail against abandoning fossil fuels. To mitigate a climate catastrophe, we need to turn to other, sustainable modes for generating the energy that we need. Renewable energy, solar and wind sources, might be our best alternative, but they are facing enormous obstacles, political resistance by the fossil fuel monopoly being one of them. But they also are linked to very high installation costs, a lack of infrastructure, particularly adequately sized power storage systems. Electricity generation from natural sources does not necessarily happen during the peak electricity demand hours and given the volatility in generation as well as load, storage is a huge, but expensive component. Lack of policies, incentives and regulations have not exactly encouraged investment into these alternative sources either.

No surprise then, that we hear renewed calls for nuclear power as a reliable, “clean” source for energy, often accompanied by the promise that the old days of large, risky plants and unsolved storage problems of radioactive waste are gone.

As if.

I attended this year’s Hanford Journey, a day focused on environmental clean-up. Hanford was an integral part of the Manhattan Project which produced plutonium for the first atomic bombs dropped in Nagasaki and released massive toxins into the ground and Columbia river where it operated. The event, sponsored by Columbia Riverkeeper and Yakama Nation Environmental Restoration Waste Management (ERWM,) made abundantly clear that nuclear waste still presents a clear and present danger to our environment and the people who live near the rivers and polluted land. We don’t even have a handle on the current dangers, and yet people are advocating for increased use of nuclear power. Some are even claiming it is our ethical obligation to promote it as the only way to combat a climate catastrophe and promising that everything will be fine with the arrival – coming soon, if you invest in us! – of small modular reactors.

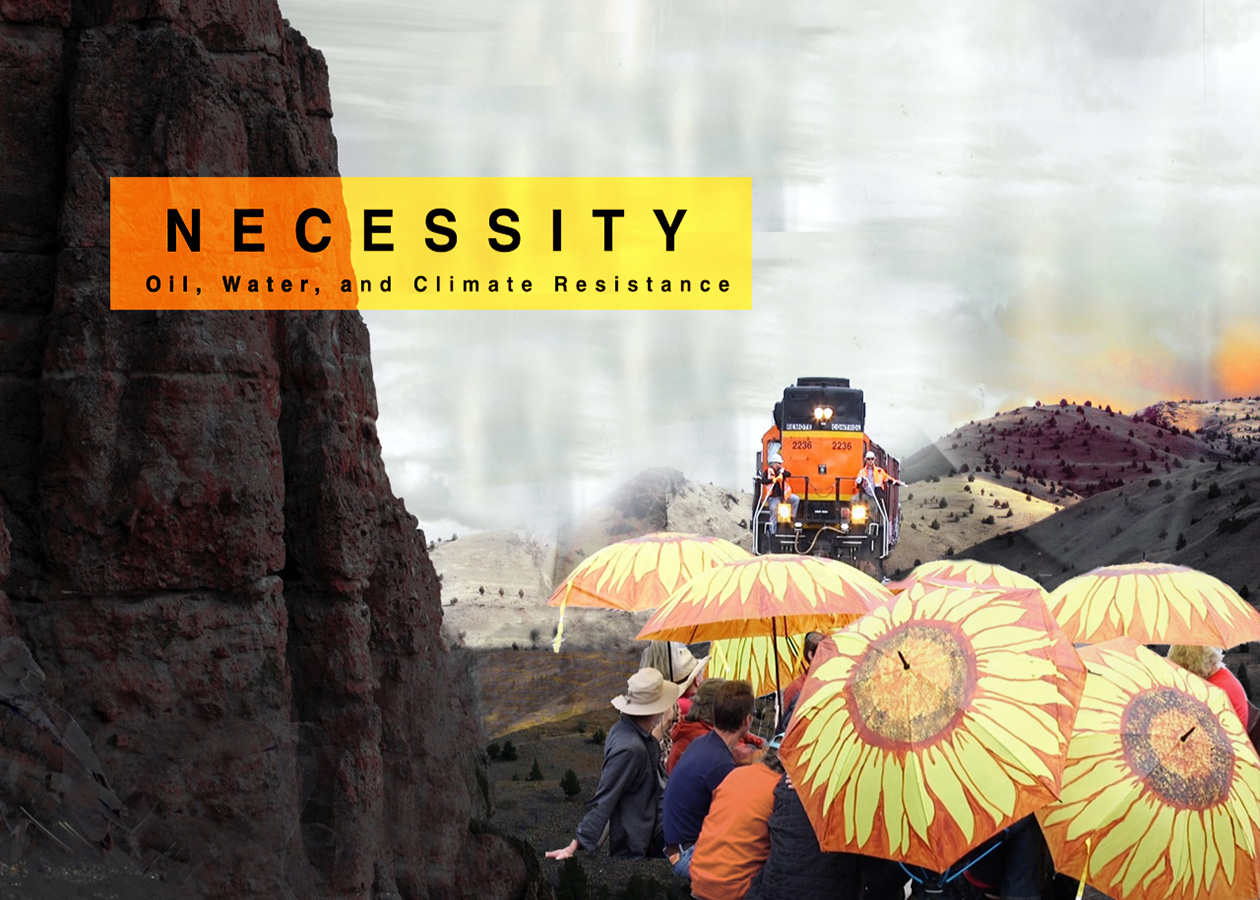

I was visiting as part of a film crew exploring the possibility of making a documentary film about the current state of nuclear power development. The interest in the topic had evolved straight out of our last films, Necessity (Oil, Water and Climate Resistance//Climate Justice and the Thin Green Line) which revealed the particular vulnerability of tribal nations to environmental pollutants. (An ArtsWatch review of the films by Marc Mohan can be found here.)

Both Hanford Journey sponsors were quite helpful in providing an opportunity for all of us to learn about the history of the clean-up efforts, view the site from boat, and talk to and hear from people who are involved in the struggle. The Yakama Nation ERWM program engages in oversight of this process and issues affecting Hanford Site natural resources. Their involvement includes participation in technical, project management, policy meetings on response and natural resource damage actions, as well as oversight of cultural resource compliance. The Columbia Riverkeeper’s mission is “to protect and restore the water quality of the Columbia River and all life connected to it, from the headwaters to the Pacific Ocean.” The organization uses legal advocacy and community organizing in numerous conservation efforts.

Map of the Hanford Site —- Simone Anter, Staff Attorney, Columbia Riverkeeper

IT WAS A BEAUTIFUL DAY, with a sense of purpose and hope delivered by multiple speakers, honoring the legacy of tribal environmental leader Russell Jim and promising to continue his mission of Hanford clean up to ensure the safety of future generations. Davis Washines, Government Relations Liaison, Yakama Nation and DNR Fisheries Resource Program for Superfund Section, talked about the history of the people indigenous to the region and their relationship with the river, the price they paid from the exposure to life-threatening pollutants and the governmental hesitancy to fully keep clean-up commitments.

Davis Washines, Government Relations Liaison, Yakama Nation and DNR Fisheries Resource Program for Superfund Section

Laura Watson, Director of the Washington Department of Ecology, evaluated how few resources are spent and how many more are needed. “The Hanford site is and remains one of the most contaminated sites in the world, and is probably the most complicated cleanup that’s ever been undertaken in human history.” Many more talked about what the situation meant for them and their families, past and present.

Kids were playing in the water, families and friends gathered for group pictures, lunch was served.

Puyallup Canoe Family

I met Ellia-Lee Jim who had been selected to be Miss ’22-’23 Yakama Nation, and chatted with Denise Reed, Puyallup and Quileutea cultural coordinator, who wore beautiful items she made with cedar weaving which she also teaches.

Ellia-Lee Jim

Denise Reed and her cedar woven hat and belt

Multiple nonprofit groups, including The Hanford Challenge and Heart of America Northwest, were on-site to educate and encourage us to become involved with ongoing advocacy efforts. A major issue right now, for example, is the Department of Energy’s attempt to reclassify high-level waste at the Hanford site to low-level waste which will allow cleanup shortcuts and unsafe disposal.

Brett VandenHeuvel, the soon-to-be-former Executive Director of the Columbia Riverkeeper (Lauren Goldberg will be his successor on August 1,) drove us from the Mattawa event site to the river, where boats, run by Tri-City Guide Service, took us out onto the Columbia and to the B reactor — one of nine plutonium reactors built at Hanford. (There was also a hike out to White Bluffs and the Hanford Reach National Monument to view the H, DR, D and F plutonium reactors, which I had to miss.)

Archeologist and ERWM advocate Rose Ferri was our guide on the boat, helping to understand the history of the Hanford Reach, one of the few remaining stretches of river where chinook salmon spawn in significant numbers, a stretch of 51 mile, to be precise, the last remaining free-flowing portion of the 1,212 miles of the Columbia.

Rose Ferri

The National Monument contains an insane number of species overall – details can be found here – all of whom depend on being protected from toxic and radioactive pollution from the Hanford site. Because Hanford is off limits to visitors, the land has been undisturbed for years, a buffer zone between ecological disaster and agricultural industries, beautiful in its sparsity.

THE HANFORD NUCLEAR SITE has been operating since 1943, after the forced removal of the people who lived on the 580 square miles on which 9 reactors were built. 1855 treaty rights to use the land for fishing, hunting and gathering, signed by the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR), the Nez Perce Tribe, and the Wanapum, were often not honored. During the 40 years of plutonium production, cesium and iodine were generated, and chromium, nitrate, tritium, strontium-90, trichloroethene and uranium, among others, leaked into the soil and seeped into the groundwater.

There were some single-shell underground storage tanks for the most dangerous liquids, but the rest flowed freely. The last reactor was shut down in 1987. Clean-up began – theoretically – in 1989 when the U.S. Dept. of Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency, and Washington State signed a Tri-Party Agreement. Only in the year 2000 were 2,535 tons of irradiated nuclear fuel in the K Basin along the Columbia River transferred into dry storage. In the following years treatment and immobilization plants were constructed, but will only be fully operative in 2023 from last I heard. Weapons grade plutonium was transferred to South Carolina.

In 2013 we learned that the single-shell tanks leak, and 4 years later one of the PUREX tunnels containing highly radioactive waste partially collapses. Ignoring these warning signs of potential catastrophe, the U.S.Department of Energy decided on a new interpretation of which kind of waste requires most stringent storage requirements in 2019.

“…. “high-level nuclear waste” (HLW) under the Nuclear Waste Policy Act (NWPA) that would exclude some dangerous waste traditionally considered HLW from stringent storage requirements. For over 50 years, the term HLW, as defined in the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 (AEA) and the NWPA, required the disposal of this most toxic and radioactive waste in deep geologic formations to protect public health. Energy’s new interpretation opens the door for less robust cleanup and the possibility of more waste remaining at Hanford.” (Ref.)

The Tribes and their allies continue to fight for a comprehensive, fully funded, thorough clean-up. Events like Hanford Journey are one way of getting informations out into the public, and familiarizing those of us who are able to attend and experience the landscape, with the history and the scientific consequences of delayed or compromised action. I wish that information could be even more widely spread.

***

I DROVE BACK TO RICHLAND, WA, across the Vernita bridge ,

and passed by a long stretched mountain, Lalíík, or Rattlesnake Mountain, that I had just seen from a very different perspective. I had been told it was the tallest treeless mountain in the world, sacred to Tribes in the region. It is designated a Traditional Cultural Property (TCP), a property that “is eligible for inclusionn the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) based on its associations with the cultural practices, traditions, beliefs, lifeways, arts, crafts, or social institutions of a living community.“(Ref.) At least that sacred mountain had been cleaned up with funds from a 2010 Recovery Act.

The whole story concerning Hanford and the depth of its operational impact on the Tribes of the region can only be understood if you have a glimpse of what it implies for their culture, never mind their existential dependence on non-toxic fish. Is that incorporated into the narratives that are officially told? I was about to find out.

***

THE REACH MUSEUM in Richland, WA, is a beautiful new structure with a mission statement that asserts inclusivity. Open since 2014, it offers various exhibits, with a permanent one on the Manhattan Project and the Hanford enterprise among them.

The staff is super helpful and friendly, the grounds are gorgeous and represent the beauty of the region. You are greeted outside with lots of affirmative information about the “clean” source of power that is nuclear energy.

You are also immediately made aware by historic photographs of trailer parks (and a real trailer) during the peak employment years of Hanford, that the region benefitted economically during times of hardship due to work opportunities. Some 50.000 people arrived at this remote region, families included. Not a mention though, there, whether these opportunities of housing and work were available to the indigenous inhabitants who were driven from their land by the Manhattan project.

The website for the museum is richly informative and emphasizes a desire to tell stories from differential perspectives and acknowledges their Native American partners “who historically used this region—a gathering place of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla, the Wanapum people, and the Nez Perce Tribe who cared for this land since time immemorial.”

As far as I could see, one statement poster, in a gallery that, overall, lays out the developments, successes and trials of the Manhattan Project (Gallery 2,) speaks to tribal presence. Acknowledging expulsion, but not going into anything further.

The focus is on the war effort,

the feats of engineering,

and the impact on Cold War developments.

Overall, a well designed, informative exhibition with a combination of local and (inter)national historical information.

To their credit, some safety considerations are mentioned, however mostly regarding the workers in an environment that was experimental in its newness, with less attention to the continuing concerns. The printed and easily accessible materials in this room were quiet about the continuing poisonous legacy and unsolved problem of long-term nuclear waste storage, however, unless I missed something, which was of course entirely possible after a long, intense day.

What would Albert think?

If you check out the educational resources on their website, the topics of Shrub – Steppe and Geologic Past are fabulously covered. In detail, comprehensive, engaging. The topics of the Hanford Legacy and Columbia River Resources are announced to be coming soon. Given the centrality of those topics as well as the controversy attached to them, in some ways, I wondered why they have not yet been designed. Your guess is as good as mine.

I have no intention to diss a museum I rather liked. I am fully aware how hard it is, particularly during this pandemic, to keep small institutions alive, much less current. But my question about how information about the continual danger of toxic environments, long-term storage of radioactive waste and un-remediated injustice of treaty betrayals reaches the mainstream, remains. This is particularly important now that calls for renewed efforts and investments into nuclear energy are getting louder. It might, or might not be a solution to our energy woes – decisions have to be based on knowledge of all the facts, though. Columbia Riverkeeper and tribal ambassadors work hard and, undoubtedly, effectively in many regards to spread the word. It is time, that the rest of us follow suit.