“You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.” – Quote attributed to Leon Trotsky but actually coined by Fanny Hurst in 1941 while addressing a rally in Cleveland, Ohio.

“First time I wore thermal underwear and a down vest to work in April,” said the museum guard standing outside Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass—a 456-foot-long concrete slot constructed on LACMA’s campus, topped by a 340-ton granite megalith. I had not expected such detailed response to my friendly “It’s cold, isn’t it?” directed at the shivering man.

Two views of Michael Heizer Levitated Mass (2012)

Glorious blue sky and sunshine were deceptive. It was cold and extremely windy when I started my visit to LACMA, exploring the grounds first, evading palm fronds flying through the air. Crazy weather, with a few of Ai WeiWei’s zodiac creatures ignoring it all and the lamps standing like frozen tin soldiers..

The shivering, alas, did not end once inside. Not due to the temperature, though, since it was quite toasty in the Resnick Pavilion. Rather, it was induced by the realization that we simply have not learned the lessons from the past – or, alternatively, have learned them all too well: media manipulation plays a significant role in preparing people for war, luring them into support for war efforts, and pulling the wool over their eyes with regards to the consequences of war. Pretending that we can know war by imagining it, is, of course, one way to sell it to the public. We might make very different decisions if we lived through the actual experience which is never matched by the most vivid imagination based on media representations. Watershed events like World War I that changed the course of history, are these days remembered as statistics – if they are remembered at all. 20 million deaths, 21 million wounded, in the span of four years (military personell and civilians combined.) Hard to intuit the nightmare that was, when only thinking about numbers.

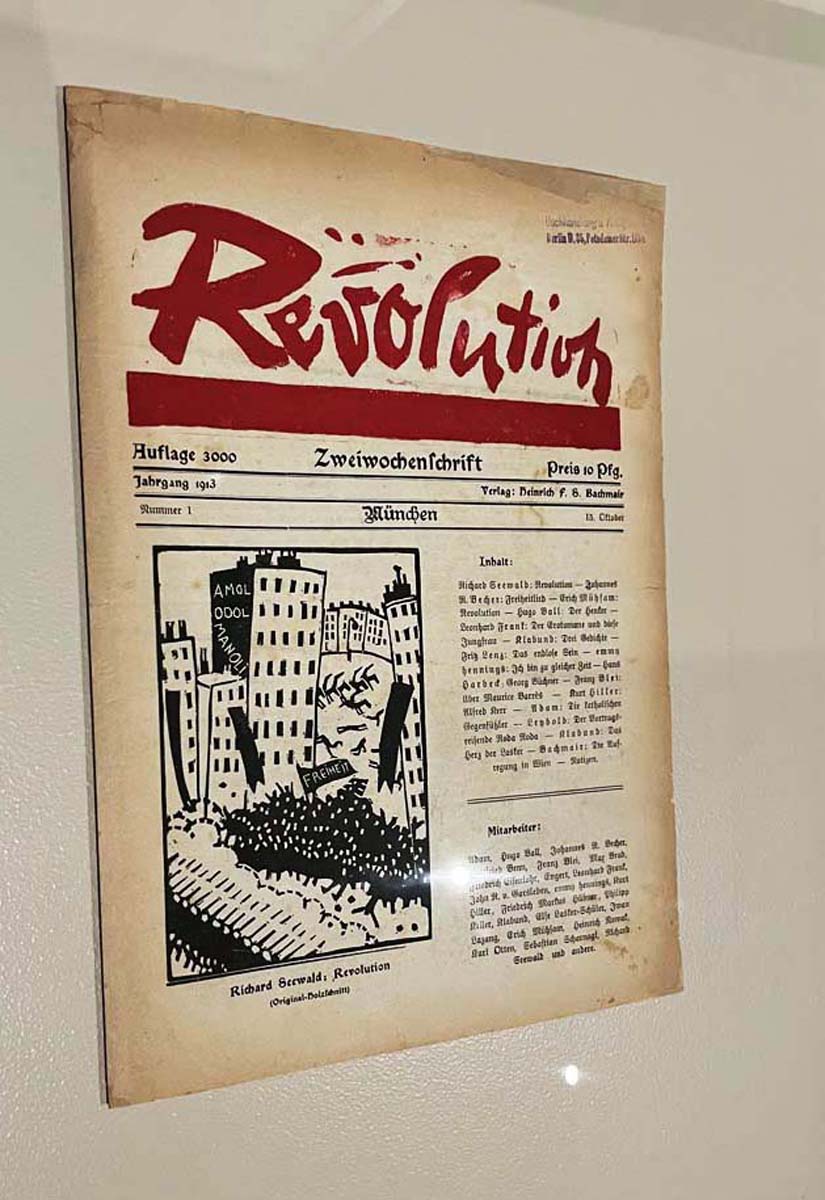

“Imagined Fronts: The Great War and Global Media,” offers some 200 exhibits chosen by Timothy O. Benson, curator of the museum’s Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies. Posters, books, rotogravure graphics, prints and excerpts from films combine to show the extent to which the public’s perception of World War I was shaped in ways beneficial to war efforts by state and private media. Inexplicably, one of the very few paintings on display was chosen to head the exhibition announcement and subsequent reviews, of which there are remarkably few. (You would think in our own time of war, the atrocities in Ukraine and Gaza, an exhibition about the interaction between media and war would be of heightened interest.)

Félix Edouard Vallotton Verdun (1917)

Maybe there is a pragmatic explanation for the choice, after all: Félix Edouard Vallotton’s Verdun (1917) spares you the reality of the slaughter that was unfolding across a full year in the French trenches (where my own grandfather fought.) It immediately lifts the gaze from the bilging smoke and fires to a bright blue horizon, as if there’s hope, something more likely to draw exhibition visitors than horror, I presume. A much more remarkable painting, Gino Severino’s Armored Train in Action (1915) is also reviewed with regularity. Based on a press photograph of an armored train, the museum signage tells us the painting is: “a celebration of a mechanized war, typifying the Italian Futurists’ extolment of the dynamics of energy and destruction.” What is conveniently left out is Severino’s eventual full-fledged support of Mussolini’s fascism.

Gino Severino Armored Train in Action (1915)

The exhibition wanders across four sections, roughly focusing on war propaganda (Mobilizing the Masses,) battle field representations (Imagining the Battlefield,) exhibits introducing the number of international forces involved (Facilitating the Global War,) and a few instances of the attempts to integrate the damage that was wrought between 1914 and 1918 (Containing the Aftermath.) Nestled in between are a few displays of those who made art or comments opposed to the war.

Overall the organization worked for me, but I found the fact that multiple movie screens, mounted up high and continuously rolling cuts of both documentary movies and propaganda films, incredibly distracting. Some of them were, as good propaganda tends to be, almost hypnotic. A German businessman encounters a woman who sells him a magic potion that will reveal “the truth” if poured on paper, before she vanishes into thin air. What appears on the previously blank page: a tank threatening armed Germans, persuading the business guy, visibly moved, to invest immediately in war bonds, so he contributes his bit as well….

The posters on display are probably familiar to many of us. Neither witty nor subtle, they capitalize on installing fear or indignation, or appeal to your compassion.

The photography section gets more interesting. There are a few memorable photographs documenting the war efforts, and the pride in new technology.

Clockwise: William Ivor Castle Canadian Troops ging over the top – James Francis Hurley Death the Reaper (ca 1918 )and Over the Top – (ca 1918.)

For me, the truly gripping parts of this exhibition were the lithographs and drawings. They can be roughly divided into those that educate, often by means of satire or inclusions of script, and those that speak to our emotions, depicting experiential suffering in hopes that it comes across.

George Grosz The Voice of the People (1927. (Money paid for the following propaganda: Hurray, Hurray!! every shot a Russian, down with Serbia, God punish England, and every Bayonet a Frenchman.)

Georg Scholz Newspaper Carriers (1922).

Otto Dix The Cardplayers (1920)

Käthe Kollwitz The Widow (1922) and The Survivors: War against War (1924)

Both trigger empathetic imagination, something that could provide a fertile ground to change views on war, realizing its futility and injustice.

Willie Jäckel Memento (1915)

“Memento 1914/15,” a blistering portfolio of 10 lithographs by Willy Jaeckel, made in 1915 when he joined the Berlin Secession to oppose artistic suppression by bellicose Kaiser Wilhelm II. (Jaeckel was just 27.) Inspired by Goya’s “The Disasters of War,” it features a reclining severed head on the cover page — the “sleep of reason” made permanent, its unleashed monsters manifold in subsequent sheets. (Ref.)

Of course, the very same mechanism, as used by propaganda posters, helps to sell war.

In some ways, this makes the exhibition thought-provoking: how easily can our imagination, needed to approximate a close representation of the war experience, be manipulated? How do propaganda posters, retouched photographs, censored prints affect our imagination? It is not just the official propaganda machine by governments, military and states, however sophisticated. It is also the art that tries to elicit compassionate imagination that played a role mostly in anti-war directions – and managed to be distributed, for the first time, in large quantities, made accessible through the modern printing presses.

ERNST FRIEDRICH WAR AGAINST WAR (1924)

The show is timely. The use of both, image manipulation for propagandistic purposes, and the employment of censorship to prohibit artists from eliciting sympathetic imagination that helps to support just causes, is ubiquitous across the world right now. Just a few days ago, the NYT reported about the chilling effects of the Gaza war on artistic expression and censorship in Germany. NPR reported on the use of misleading videos (old or from video games) flooding the social media to escalate tensions between Palestinian and Israeli supporters, just a few days after the horrific Hamas attacks. Pro-Israel sources claim “Pallywood Propaganda,” accusing Palestinians of staging or faking their suffering.

El Dschihad, no. 25, January 25, 1916, in German prison camp created for muslim soldiers – Raoul Dufy The Allies, (c. 1915) – Lucien Jonas African Army and Colonial Troops’ Day, (1917)

Our increasing awareness of AI’s power in creating deep fakes leads us to discount the veracity of purported eyewitness accounts, sent via videos out of the war zones, with few means of assessing what is real and what is false. That uncertainty, in turn, can lead to a general disavowal of visual reports, a lack of trust that opens doors to political manipulations by those who claim they, and they alone, can guide us to “the truth.”

Art is related to conflict in so many ways – during wars, art is looted as a trophy, art is destroyed as a way of demoralizing opponents, it is used, as mentioned before, as a tool of propaganda in order to generate both psychological and material support for the war effort. Can art that opposes war, as expressed in writing, visual representations, music, really make a difference in our day and age, given our distrust, our being overwhelmed, our dire need to avoid being flooded and wanting to distance ourselves from war imagery? When war defeats the imagination, can art rekindle it? Can it cut through hate, anger, resentment, violence and destruction, change minds? The debate is ongoing.

Sergio Canevari The Russian Peace (1918)

I have no definitive answer. This exhibition’s imagery most meaningful to me, a pacifist, namely the depictions of suffering and the satirical stabs at those who financially gain from war, will likely not speak to those eager to go to war, just like racist propaganda posters embraced by them do nothing for me. Maybe our ideological or political divisions prevent us to think through art that does not confirm our preexisting beliefs. To that extent, art will not be able to produce change, given the strength of our biases. (I have written about this at length recently, as you might remember.)

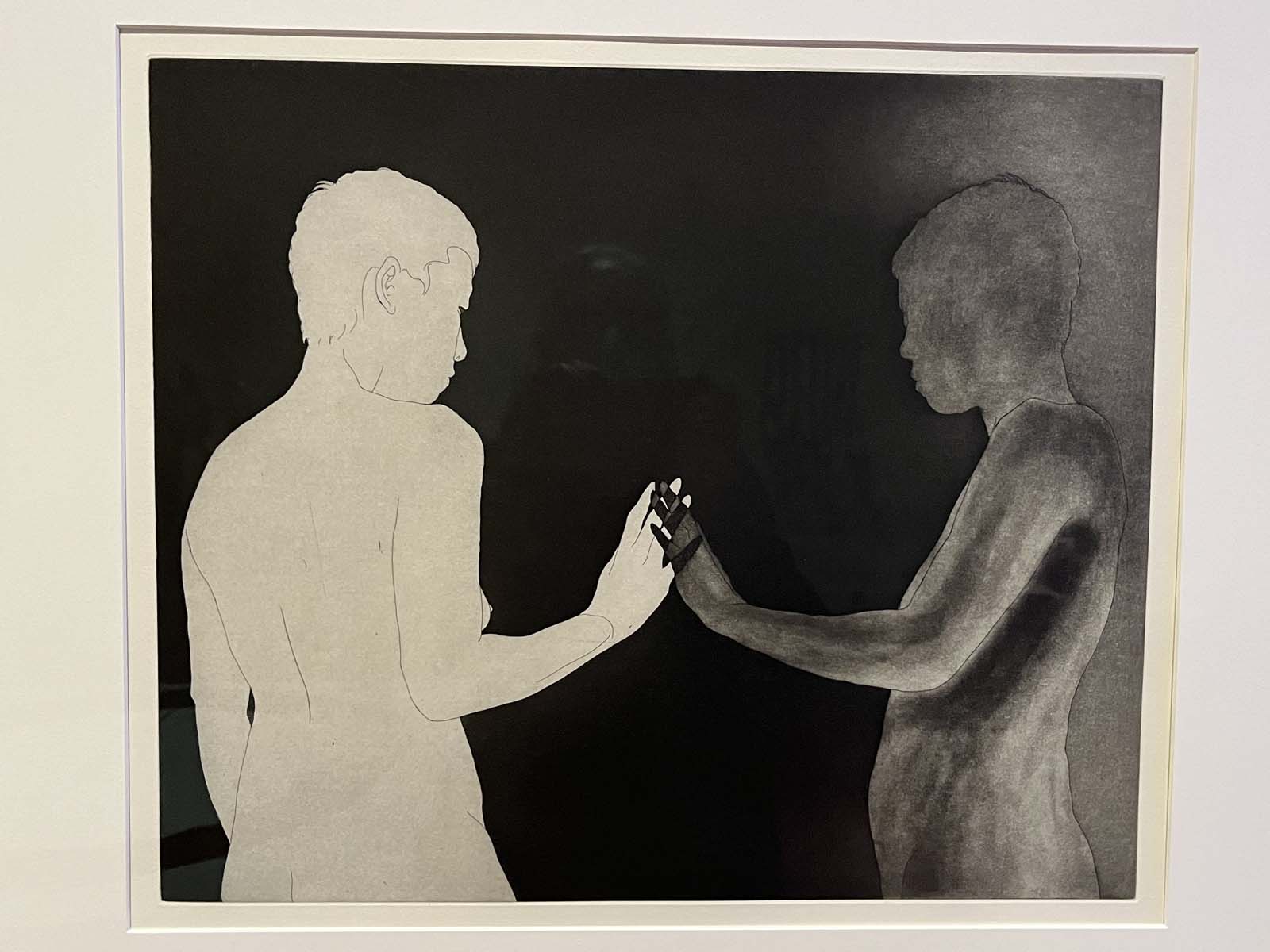

Pierre Albert-Birot Final study for The War (1916)

However, if I consider what happens when I share the art that appeals to me with other people who are open to it, it surely creates a sense of solidarity and feeling of belonging to that group. Maybe it guides you to find your kind, to strengthen a movement, to empower you to speak up for shared values. If controversial art models courage, it might spark you to be brave and resist, as well. Not a small feat.

Johannes Baader Dada-Dio-Drama (1920)

Right now we look from afar at wars in Ukraine, in Gaza, in Tigray, in Sudan, Syria, in Lebanon, with more on the horizon, should Iran, China, Russia, North Korea, the U.S. or Nato advance to increasing military action. We might not be interested in war, but war will be interested in us. And at that moment we will need allies to resist its pull, some of whom, just maybe, can be found through a shared appreciation of the relevant art as well as shared forms and intensities of imagination, allowing us to keep a critical perspective and fight manipulation.

Am I optimistic about this? Not really.

Hopeful? You bet.

Otto Schubert Watercolor, pen. and pencil on postcards he sent to his future wife. Off to War, November 18, 1915, Fire, Explosion, December 1, 1915 Evening Mood at the Front, January 24, 1916 Argonne, French Prisoners, April 1, 1916 Hot Day at the Front, April 7, 1916

Imagined Fronts: The Great War and Global Media

December 3, 2023–July 7, 2024

Resnick Pavilion

Los Angeles County

Museum of Art

5905 Wilshire Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA 90036

Edward Kienholz The Portable War Memorial (1968-70)