When you travel, even for longer stretches of time, you have to make choices. So much to explore, to learn in Los Angeles, this behemoth of a city – there has to be some selectivity, since not all can be fit in. My own selections are usually based on two basic considerations: get familiar with the history of the place and, of course, seek out stuff that feeds my specific interests, art and politics, as you well know.

I lucked out last week with these endeavors in more ways than one. To understand the history of the greater Los Angeles area, I had read Mike Davis‘ City of Quartz: Excavating the Future of Los Angeles (1990) and slogged through his last book, Set the Night on Fire. L.A. in the Sixties (2020), published before his death in 2022 and co-authored with Jon Wiener. Both are seminal works about the urban history of the place and the powers that shaped it since its inception. Cultural critic, environmental historian and political activist Davis described the intersection of land development and legal or functional racial segregation in Southern California in ways quite accessible to uninformed readers like me, basing his account on interdisciplinary sources, including American history, environmental history, Marxist philosophy, political science, urban geography, architectural and cultural studies. Both books introduce the forms of resistance to segregation in housing and education, from peaceful demonstrations to riots to the engagement of artists and other intellectuals, side by side with famous civil rights fighters, political organizations, union representatives, the ACLU and uncountable numbers of students as young as high school freshmen.

88 cities, approximate 140 unincorporated areas, and communities within the City of Los Angeles.

The author introduces us to the political economy that shaped the urban sprawl, the landscape transformation, resulting in increasing inequality of living conditions and incarcerations rates, making it a dystopian place for those who fell off the wagon of the American Dream, or shall we say, were pushed off by the interest of those defending Fortress L.A. from any influx of non-White and/or poor populations. Land, seemingly endless land was the commodity, providing the base for residential neighborhoods, industry, strip malls and freeways. Richer neighborhoods, in fear of losing their exclusivity, the down-town commercial district’s business owners and realtor- and home owners’ organizations collaborated with investors, local and state politicians, and even Roman Catholic church leaders to make decisions about land-use that protected the interest of the monied classes and ended up with unimaginable sprawl.

Even though fair housing laws existed, racism won when Proposition 14 was adopted by an overwhelming majority of California voters in 1964, scorning equality and discriminating against “undesirable” homeowners and renters who were now easily excluded. The vote allowed prior law, the California Fair Housing Act of 1963, also known as the Rumford Act, to be voided, creating a state constitutional right for persons to refuse to sell, lease, or rent residential properties to other persons. (The Supreme Court declared the Proposition unconstitutional in 1967. The current legal status can be found here.) It was a pivotal moment that brought the efforts of many organizations and individuals fighting for civil rights to a screeching halt at the time.

Later decades saw more subtle ways of achieving the same goals of segregation: zoning laws and security measures kept the poor away from affluent districts. Relentless and cruel, often violent policing kept particularly Black citizens and other POC in their allotted places, both literally and metaphorically. Zoning was also causal for pushing the non-White and poor populations to the perimeters of the county, within or adjacent to more dangerous environments when it comes to pollution, water shortage and now fire danger given climate change-enhanced droughts. I am summarizing these aspects of Davis’ books because it was striking for me to see the described social stratification play out in real space during a drive to East Los Angeles College, a public Community College in Monterey Park, CA.

East Los Angeles College, Monterey Park, CA.

I started in the heart of Pasadena’s historical district, a place full of beautiful, gorgeously maintained and lovingly restored mansions, then drove through the picture book landscape of Pasadena’s craftsman bungalows. 15 minutes later you come through small townships that still have single-lot houses, but now run down and clearly showing signs of economic distress. Another 20 minutes along, and you are surrounded by low income housing apartments. I parked in a strip mall adjacent to the college and was immediately taken in by a striking building that stood out against the dilapidated background: the Vincent Price Art Museum. Part of a Performing and Fine Arts Center that opened in 2011, the museum holds a permanent, major collection of fine art, with substantive work initially donated by actor Vincent Price (he of Hollywood Horror Movie fame, among others, but also a true friend to the arts and the educational efforts required to bestow knowledge of art and art history onto future generations.) By now the museum holds over 9000 objects and has hosted more than 100 shows, singular for a community college, its exhibitions thoughtfully and smartly curated.

I came to see one of them that seemed particularly aligned with the museum’s expressed mission and issues close to my own heart concerned with cultural diversity and critical thinking:

“The mission of the Vincent Price Art Museum at East Los Angeles College is to serve as a unique educational resource for the diverse audiences of the college and the community through the exhibition, interpretation, collection, and preservation of works in all media of the visual arts. VPAM provides an environment to encounter a range of aesthetic expressions that illuminate the depth and diversity of artwork produced by people of the world, both contemporary and past. By presenting thoughtful, innovative and culturally diverse exhibitions and by organizing cross-disciplinary programs on issues of historical, social, and cultural relevance, VPAM seeks to promote knowledge, inspire creative thinking, and deepen an understanding of and appreciation for the visual arts.

What Would You Say?: Activist Graphics from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art presents a selection of political prints from LACMA’s vast archives. The exhibition, which opened March 25th, is free of charge and the visitor gets gifted with a high-quality brochure, covering some of the art with prints and explanatory (bilingual English/Spanish) text that I found helpful.

Graphic art has traditionally been a vehicle for change, challenging as well as influencing political moments. Rather than just depicting, the combination of image and word can inform, comment, persuade or be used for propaganda. It has been a key player in protests against injustice and oppression; the fact that it can be easily, widely and cheaply created and distributed has made it a form that helps to connect to people and promote social change. In the late 19th century, the technology for lithographic printing advanced, and the new power-driven presses, practical techniques of photoengraving and mechanical typesetting devices helped the medium to progress. We have now added photo-typesetting, offset lithography, and silk screening to the repertoire. It has also often been a communal effort, linking artists and participants with shared goals and interest, helping to organize and to educate.

The graphics on the wall ranged from the mid 1960’s to the 2020s, covering the Black Panther’s fight against police brutality and for the empowerment of poor Black neighborhoods,

Left: Emory Douglas Untitled (Sin Titulo) 1970 – Right: Rupert Garcia Libertad para los prisoneros politicas! 1971

the issues of incarceration of innocent people and Latino activism,

Yolanda M. López Free Los Siete 1969

Jessica Sabogal Walls can’t keep out Greatness 2018

the struggle of women and immigrants for equality,

Clockwise from upper left: Yreina D. Cervantez La Voz de la Mujer 1982 – Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, Women in Design: The next Decade 1975 – Yreina D. Cervantez Mujer de mucha enagua 1999 – Krista Sue Pussy Power Hat Pussy Hat Project 2016 – Ernesto Yerena Montejano and Ayse Gursoz We the Resilient 2017

and eventually the protests over the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and other Black people by police.

Jesus Barraza and Melanie Cervantes of Dignida Rebelled and Mazatl My Name is Trayvon Martin and my Life Matters. 2013

The most dominant topic, however, is expressed in posters and prints protesting war; surprisingly, I could find the issues of racial segregation and land development, so central to the history of L.A. and S.F., only peripherally – one poster about evictions, and one about the displacement of first native people and then a Mexican American community from Chavez Ravine, land appropriated to build the beloved L.A. Dodger stadium.

Favianna Rodriguez Community Control of the Land 2002 – Vote Ik We are still here 2017

The reality of racism, however, is captured by several of the works in ways that hit you hard.

Archie and Brad Boston For a Discriminating Design Organization 1966

David Lance Gaines Qui Tacet Consentit (Silence Gives Consent) 1969

The reality of the price of war, on the other hand, is brought home most strikingly in a print by one of the most famous of the artists in this exhibition, Sister Corita Kent, a member of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (IHM) before she was driven out by Cardinal Francis McIntyre (as were later 90 percent of the order in L.A, some 150 IHM nuns kicked out. According to a report in the Times, the Cardinal, by the way, uttered these words when confronted with his stand on segregation: “…it is not a racial or moral issue. A reason for discrimination is that white parents have a right to protect their daughters…”)

Corita Kent manflowers 1969

Corita Kent’s early silk screenings used bright colors, modulating the style and objects of advertising as stand in for religious concepts. They were shown in galleries and museums across the country, the MET, MOMA and LACMA included. She later moved to political topics, with more muted colors, including the Watts Rebellion and, after multiple encounters with anti-war activist Dan Kerrigan, the Vietnam War. The poster here shows two blinded soldiers, using Peter Seeger’s song lines in despair. Man-power is broken into two words, drawing attention to the single man, all the individuals that made ups the military power, paying with their bodies or their lives.

Posters on video display. The last one above: Primo Angeli/Lars Speyer The Silent Majority 1969

***

I wondered, a few days later, if the choice of concentrating on so many war/peace posters in the VPAM exhibition was perhaps linked to the choices made in another, simultaneous exhibition of graphics from the LACMA archives: Pressing Politics: Revolutionary Graphics from Mexico and Germany.

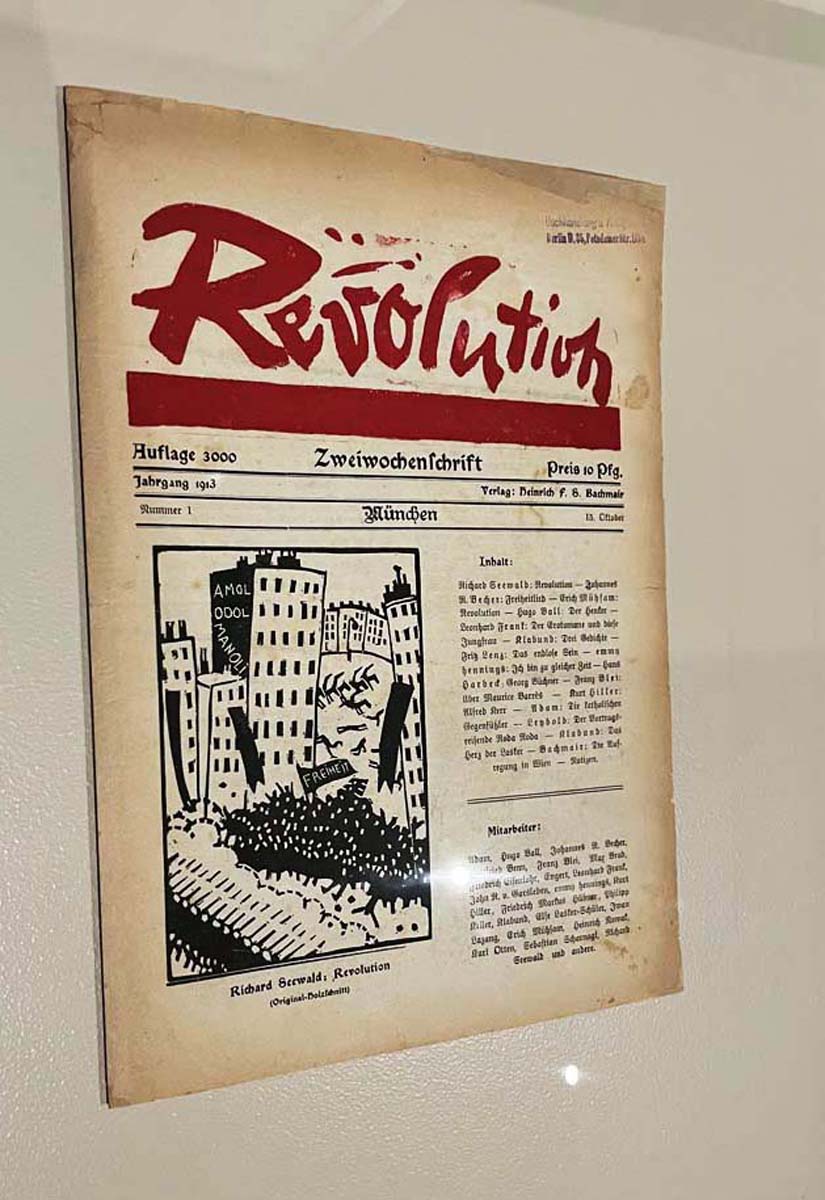

This exhibition is also shown in a gallery incorporated within an educational setting, this time the Charles White Elementary School on Wilshire Blvd. It presents political imagery that grew out of the reaction to war and revolutionary movements, from Germany’s political developments starting in 1918, to Mexico’s 1930s formation of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (People’s Print Workshop) in Mexico City.

For me it packed an additional emotional punch – I have grown up with the art of Kollwitz, Grosz, Pechstein etc. in post-war Germany and the familiarity and reminiscence of what they meant then added a layer to taking the show in. To look at the warnings expressed by art in the 20s and 30s, to know that the world was dragged into the next war regardless, and to see all this while we are witnessing another contemporaneous war on European soil was unsettling. The unsparing depiction of oppression, violence and human suffering is also strikingly different from most of the American poster selection in the show discussed above.

Some of the graphics would benefit from explanations regarding the relevant language. Take Grosz’ Gesundbeter, for example, which has three titles in different languages (he used these inscriptions fully knowing that they were not translations but expressed different thoughts.) Crucially, though, the obscenity of the action becomes clear when you understand the acronym KV, central to the image. It stands for the German word Kriegs-Verwendungsfähig – literally usable for war or fit for action, applied by the Local Board, desperate for canon fodder, obviously even to corpses.

George Grosz Die Gesundbeter 1918

Here is another title – the German says sunshine and fresh air for the proletariat (a demand by labor unions and social activists for better housing and healthier working conditions,) depicting incarcerated people walking the prison yard.

George Grosz Licht und Luft dem Proletariat 1919

The parallels we see in the German and Mexican depictions originate both from shared experiences, but also an overlap of artists in each others’ spheres. Colonialism led to an entangled history in general, but during the 1930s many German artists associated with the Staatlichem Bauhaus Weimar emigrated to Mexico, welcomed by the government of Lázaro Cárdenas del Río (1934–1940) which built the most democratic state historically experienced in Mexico until the 1990s.

Clockwise from upper left: Alfredo Zalce En Tiempos de Don Porfirio 1945 – Alfredo Zalce La Soldadera 1947 – Käthe Kollwitz Losbruch 1943 – Leopoldo Mendéz Asesinati de Jesus R. Menendez en Cuba 1948 – Käthe Kollwitz Gedenkblatt für Karl Liebknecht 1919-20.

The Cárdenas government sponsored educational program for workers and peasants, led by the Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (LEAR), an association of revolutionary writers and artists that grew out of the “cultural missions” charged with propagating the revolution’s objectives in murals, graphic art and theater productions. The Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) came out of this association, and was revitalized by the many migrants that came from Europe, other Latin American countries and the U.S., all adding their own cultural experiences, artistic styles, and preoccupations. In fact, Hannes Meyer, second Bauhaus director, was appointed as head of TGP in 1942.

Erasto Cortez Juarez, Jesus Escobedo, Leopoldo Mendez, Francisco Mora Calaveras aftodas con medias naylon 1947

Leopoldo Mendez En manos de la Gestapo 1942 – Constantin von Mitschke-Collande Freiheit 1919

Arturo Garcia Bustos La industrialización del país 1947

It is a stunning exhibition, offering diversity of depictions balanced by homogeneity of concerns. I was the only one there on a beautiful Saturday afternoon, except for a friendly guard, which was just as well given the tears that welled up. The reality of war, the repeat of history’s darkest moments seemingly unavoidable, some already here, some looming, the resurgence of fascistic ideas and methods seemed to pull the rug out from under the efforts of earlier artists to warn us of dangers and call for change.

Erich Modal Revolution 1920 – Max Pechstein An die Laterne 1919 – Unknown artist: So führt euch Spartakus. Brüder rettet die Revolution. 1919

And yet. There is reason to remain optimistic. Individual commitment to social change still exists. But not just that – in L.A. alone, there have been significant collective successes across the last years. In 2006, 500.000 people protested on Wilshire Blvd. demanding rights for undocumented immigrants, a march called by labor unions, endorsed by catholic Cardinal Roger Mahoney and Antonio Villaraigosa, the city’s first Latino mayor. In January 2017, 750.000 congregated downtown L.A. for the Women’s March. And in 2019, large coalitions of communities and classrooms, teachers and students joined in the successful teachers’ strike that focussed on overcrowded schools, educational disinvestment and drainage of resources to charter schools.

Leopoldo Mendez Retrato de Posada en su taller 1956

Elizabeth Cattle Sharecropper – 1952 – Alberto Beltran El problema agrario en América Latina 1948 – Käthe Kollwitz Poster excerpt

Max Pechstein Dont strangle the newborn freedom through disorder and fratricide, or your children will starve 1919.

Walking around the neighborhood after I left the exhibition, the occasional public or street art made it clear that activism is alive and well. A work in progress, standing on the shoulders of the many activist artists who came before. Grateful that decisive museal curation introduces and reminds us of the modernist vanguard.

- Mar 25–Jun 24, 2023

- Vincent Price Art Museum

1301 Avenida Cesar Chavez

Monterey Park, CA 9175

Pressing Politics: Revolutionary Graphics from Mexico and Germany.

- Oct 29, 2022–Jul 22, 2023

- Charles White Elementary School | 2401 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90057

- 1 – 4pm on Saturdays

Louise Palermo

First of all, I felt like I was walking along side you viewing each artwork. What a rich, provocative day you shared. LA is a tapestry of conundrums and beauty, politics and poshness, extreme wealth and poverty. This blog is insightful on steroids…Like many Angelenos.