Less reading, more listening today. That is, if you’re inclined to follow me down the rabbit hole that opened up when I searched for sounds relevant to today’s images of the Pacific ocean at Malibu Beach, CA.

I came upon the field recordings of Sam Dunscombe, who mixes his music with environmental sounds collected across the world. If you click on the link, an album appears that has one track of forest noises and one of oceanic sounds.

The second one (O) is the one you want to listen to while perusing the photographs, oceanic sounds that calm (unless you cannot stop thinking about what a Tsunami or rising sea levels would do to the beach houses, or about the yellow line on the horizon that is light reflected in thick bands of pollution. (I know, can’t I just simply enjoy a sweet day at the beach? You know me.)

In any case, I read up on Dunscombe and encountered the musical concept of Just Intonation a phrase that sounded lovely. No worries, not trying to explain it, it’s too hard for my tired brain (here is an introduction, if you are curious.) Suffice it to say there is a community of researchers, composers and musicians who explore this specific way of notating music by giving pitches as fractions and focusing on pure, natural harmonics, and he is actively part of such a group in Berlin.

While trying to wrap my mind around it, I learned that this tuning system was used in medieval music that used melodies only, but proved impractical for polyphonic music that we’ve enjoyed for the last many centuries. Yet composers are aware of it, and that, in turn, led to a pointer that mentioned Benjamin Britten, who had written a piece that in its prologue and epilogue uses the horn’s natural harmonics. I had never heard this Serenade, and was bowled over while listening.

The Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, Op. 31 is not just musically riveting in its marriage of tenor and horn, but the lyrics of the song cycle are also timely: six poems, ranging from an anonymous 15th-century writer to poets from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, describe aspects of the night: from serene setting to the horrors emanating from the dark. Written in 1943 during World War II, with bombs raining down, the darkness of night took on a different weight, and the sinister feelings are conveyed to perfection. Once again I am struck by how words depict, while music expresses, making the layers that are indescribable felt nonetheless.

This music transcends into our own time of war, even for all of us who sit in the safety of our homes, and it should help to raise levels of empathy. Night invoking sleep, the final sleep brought by war to its victims, their souls in flight, in contrast to those who profit from it in so many ways in broad daylight, unimpeded.

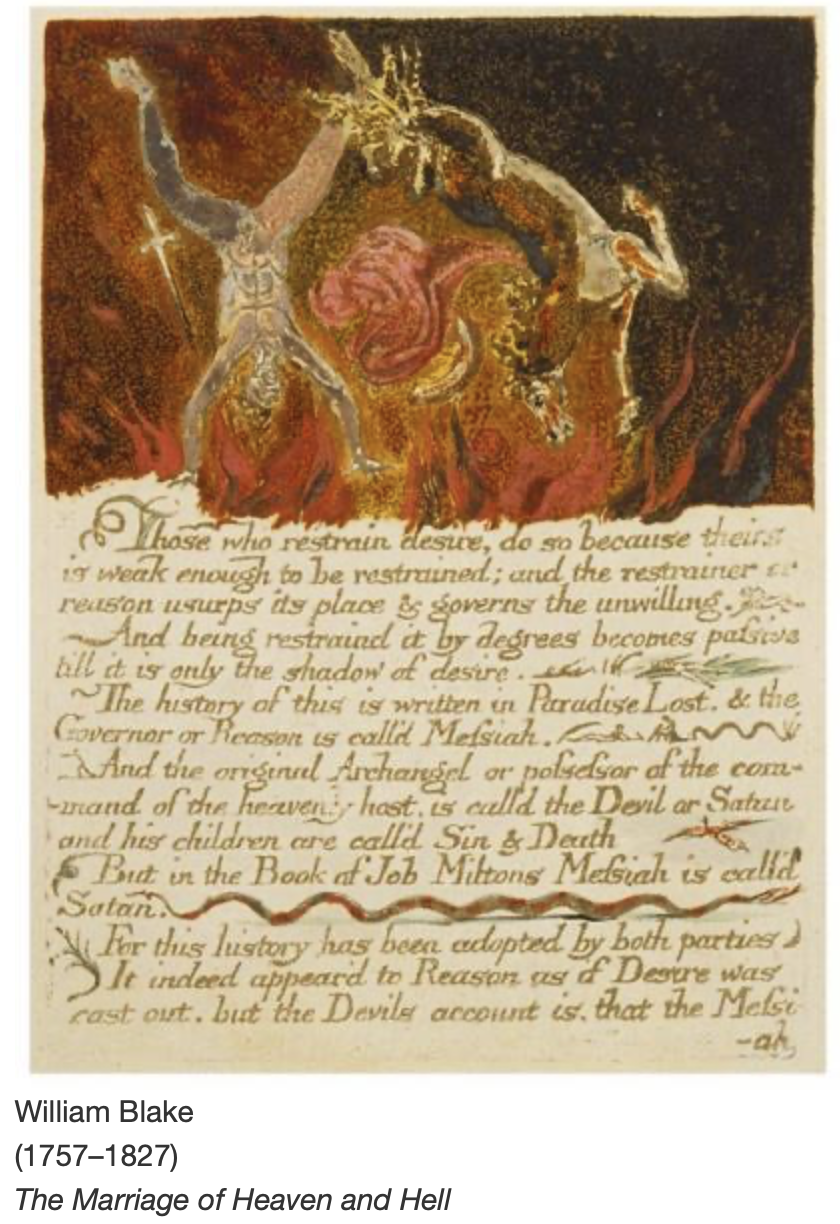

Here is one of the poems Britten used. (I picked William Blake, since I had just reviewed his work in these pages a couple of weeks ago.)

Elegy

O Rose, thou art sick;

The invisible worm

That flies in the night,

In the howling storm,

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy;

And his dark, secret love

Does thy life destroy.

William Blake (1757–1827)