Art On the Road: Made in L.A. 2023

· The Act of Living at the Hammer ·

“At its outset in the mid-1960s, the historic preservation movement contributed to the racial splintering of the nation’s urban fabric. It denied the freeway’s entry into communities deemed historic while granting its passage through communities judged differently. It empowered some communities in their fight against the freeway while putting others at a disadvantage. In the disproportionate number of black communities that bore the brunt of urban highway construction, the preservation strategy had no chance, leaving displaced residents with a meager set of resources to recuperate their connection to the past. This is why we need to pay attention to murals, festivals, autobiographies, oral histories, and archival efforts. In the high-stakes struggles over the fate of the American city, these were the “weapons of the weak,” the tools invented by displaced communities to fight the forced erasures of their past.”

― Eric Avila, The Folklore of the Freeway: Race and Revolt in the Modernist City

WHEN YOU ARE NEW to a city, like I am to Los Angeles, one way of exploration is to hit the history books. I had described my early mapping of the city onto Mike Davis’ City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles in April here, while reviewing an exhibition from the LACMA archives, Pressing Politics: Revolutionary Graphics from Mexico and Germany.

This time, I brought Weimar on the Pacific: German Exile Culture in Los Angeles and the Crisis of Modernism by Ehrhard Bahr, thinking I might follow in the footsteps of my exiled Landsmen during the 1940s, artists and intellectuals fleeing Nazi persecution. The book’s introduction contains the following description: “Los Angeles has occupied a space in the American imagination between innocence and corruption, unspoiled nature and ruthless real-estate development, naïveté and hucksterism, enthusiasm and shameless exploitation.”

I don’t know about the American imagination, but those of us who devoured Berthold Brecht’s California poetry 20 years later as German teenagers obsessed with America were undoubtedly influenced by his assessment:

Contemplating Hell

Contemplating Hell, as I once heard it,

My brother Shelley found it to be a place

Much like the city of London. I,

Who do not live in London, but in Los Angeles,

Find, contemplating Hell, that it

Must be even more like Los Angeles.

Also in Hell,

I do not doubt it, there exist these opulent gardens

With flowers as large as trees, wilting, of course,

Very quickly, if they are not watered with very expensive water. And fruit markets

With great leaps of fruit, which nonetheless

Possess neither scent nor taste. And endless trains of autos,

Lighter than their own shadows, swifter than

Foolish thoughts, shimmering vehicles, in which

Rosy people, coming from nowhere, go nowhere.

And houses, designed for happiness, standing empty,

Even when inhabited.

Even the houses in Hell are not all ugly.

But concern about being thrown into the street

Consumes the inhabitants of the villas no less

Than the inhabitants of the barracks.

Bertolt Brecht Nachdenkend über die Hölle, 1941, translated by Henry Erik Butler

Mural and Paintings by Devin Reynolds on the walls of the Hammer lobby. Contains references to John Milton’s Paradise Lost, displacement from a beautiful home acting as a red thread through the histories of many Angelenos.

Many decades later I wholeheartedly disagree with Brecht’s description – I find L.A. vibrant and fascinating – though not his political analysis. He knew class divisions and precarity when he saw it. By all reports, he clung to negative emotions as a motor driving his writing. But his ability to pick up on what makes this city thriving, underneath capitalistic excess or popular culture driven by interests to keep racial segregation intact, might have been curbed by what was then and still is not easily visible to the outsider. At least that is my speculation after chancing on Eric Avila’s The Folklore of the Freeway: Race and Revolt in the Modernist City, from which I cited at the very start of these contemplations.

Knowing the history of a place is essential to understanding its character. Who rose to the top and who was pushed to the bottom will define the nature of both the lay-out, the (d)evolution of neighborhoods and the way power hierarchies are distributed. My hometown of Hamburg, Germany, for example, needs to be read in the context of its merchant marine and membership in the Hanseatic League, its intermittent warfare with Scandinavian neighbors, and its destruction under Allied firebombing during World War II.

Left: Marcel Alcalá Right: Emmanuel Louisnord Desir

There are ways of learning about the past of a city and her people that are not found simply by looking in all the traditional places. Clearly, mainstream historians have little incentive to document attempts towards self-empowerment or organized resistance by those not among the ruling classes. Facts about the past are instead often woven into the fabric of experienced daily life, painted on neighborhood walls (I had written about Pacoima, for example, here,) told during story time in corner libraries, experienced during Saturday’s soccer matches at the local park, found during celebrations of special days for different nationalities. Not just the past, I’d add, but the present, as it resurrects what was to be extinguished. Not exactly easily accessible to a foreigner like Brecht, struggling with the language, not particularly mobile, traumatized by persecution and exile, and facing the fact that there are 88 cities, approximately 140 unincorporated areas, and communities within the City of Los Angeles.

Jibz Cameron Cops, Coyotes, Cars, Crows (2023) Watercolor, Correction Fluid and Graphite on Paper

We, on the other hand, are lucky enough to find quite a bit of it all in one place, a weave that is compact as well as sprawling, screaming as well as whispering, consciously representing or intuitively describing, like L.A. itself. It’s made possible by curators who brought a cross section of yet undiscovered stories into an exhibition that in many aspect mirrors the city it drew from.

At least that is how I experienced the Hammer’s current exhibition Made in L.A. 2023: The Act of Living, an iteration of its biennial attempt to showcase new talent, unknown or underrepresented artists, providing access to what is likely hidden to most of us from different cultural enclaves. Guest curator Diana Nawi and Pablo José Ramírez, who joined the Hammer museum full-time in June, and Ashton Cooper, Luce Curatorial Fellow, have assembled some 250 works of 39 locally based artists, challenging us to confront our stereotypes and navigate an abundance of thought-provoking art. I come back to what I had written about our own Portland’s current art extravaganza, Converge 45: perceptive curation is a mystery to me, like herding cats, but when it succeeds it is a gift to the community (never mind an intellectual feat.)

Their guiding principles can be found in their statement above.

***

AT RISK OF FALLING for surface rather than structural characteristics, here is an analogy I can’t resist: as L.A.’s neighborhoods differ along multiple dimensions, so does the chosen art in this show. By size, by spacing, by density, by degrees of familiarity. Just as I like some neighborhoods more than others, some leaving me cold, some moving me to the core, some eluding my comprehension, some dull, some riveting, some evoking scorn, and others longing or admiration, so it is for much of the work on display. What registered most deeply was the fact that many of the exhibits taught me something I would not have otherwise known, and how much, sometimes viscerally, texture ran as a common theme through the galleries. Texture, indifferent to past, present or future, is, of course, a stand-out characteristic of Southern California’s nature for this Northerner, with its unusual mix of desert and tropical plants, all ridges, grains, thorns, spines and spikes, peeling bark, twisted fronds, and leathery surfaces.

Kinetic sculpture by Maria Maea “Lē Gata Fa’avavau (Infinity Forever)” (2023) including parts of palm trees, car parts and feathers.

Really, I think there are few materials known to man not included in this biennial. Natural materials like wood, bones, wool, cotton, pearls, wax, mica, graphite, dirt, salt, limestone, copper, leather, feathers, palm fronds, sea shells, corn, corn or other plant based substances. Fabricated materials like acrylic, plastics, paper, forged metal, glass, lead alloys – you name it, it was affixed or served as a constituent even in the context of more traditional forms of painting. Some assemblages consisted of more material detail than you could possibly take in at a single visit. Videos were (blissfully) few and far in-between, although demonstrations of octogenarian Pippa Garner triggered some giddiness.

What follows are some photographs to relate the overall variety of art on display, not necessarily work that I liked, but work that speaks to the range of cultural production, the focus on texture, as well as entryways into histories new to me. I will then turn to my absolute favorites, both artists I had never heard of. In one case, apparently, the same was true for the curators, who only met the young painter upon recommendations of other studios.

Beautiful weavings by Melissa Cody, Scaling the Caverns (2023) at center, detail below

Sensuous configurations of leather, painting- or quilt-like, by Esteban Ramón Pérez,

Esteban Ramón Pérez Cloud Serpent Tierra del Fuego) (2023) Leather, rooster-tail feathers, urethane, acrylic, nylon, jute wood.

Disquieting collages by King Seung Lee,

Kang Seung Lee Untitled (Chairs) (2023) Graphite, antique 24-k gold thread, same, pearls, 24-k gold leaf, sealing wax, brass nails on goat skin parchment, walnut frame.

(Aside: what it is with chairs that can so easily register as ominous? Look at Tadashi Kawamata‘s currently exhibited at Liaigre’s building in Paris: Nest at Liagre. Or is it just me?)

Photo creditL Sylvie Becquet

From the younger set:

Michael Alvarez 2 Foos and a Double Rainbow (2019) Oil, Spray Paint, Graphite and Collage on Panel

A reminder for those of us who vicariously experienced the AIDs epidemic as young adults when living in NYC, with friends dying:

Joey Terrill works, the selection depicting formative memories and daily experience in queer communities.

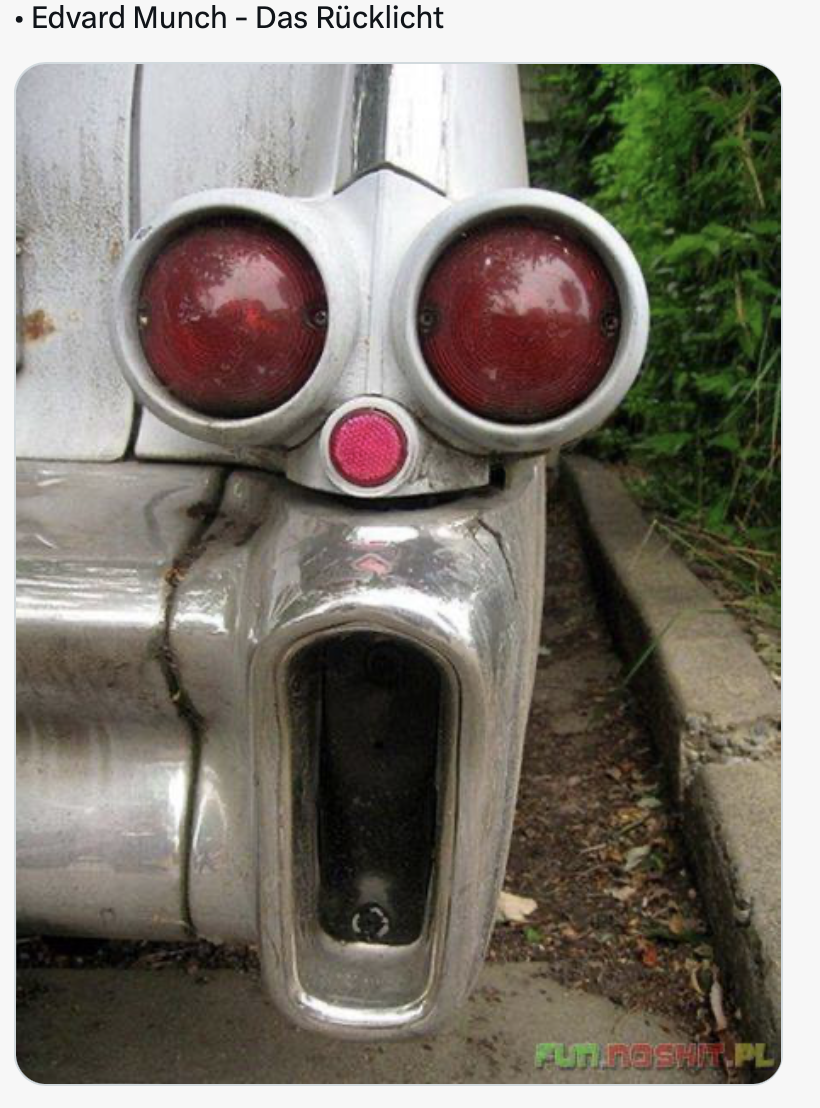

The Munch-inspired scream on steroids below attracted a lot of attention, justified, in my opinion, only if you looked more closely on the backside of the sculpture that provided a narrative worth the attention grabbing. The sculpture was co-created by numerous Native Americans.

Ishi Glinsky Inertia – Warn the Animals (2023)

Runner-up to the works below that inspired me most, was this assemblage using a silk parachute. Talk about texture!

Erica Mahinay Lunar Tryst (2023) and Details. Acrylic, raw pigment and aluminum leaf on half-silk parachute, lead, ostrich feathers.

And here are Kyle Kilty’s paintings, as vibrant, patterned, and hibiscus-colored as L.A. itself, capturing the imagination with abstractions that turn representational upon closer inspection – just about the same process the traveler experiences when getting to know and learning to navigate this moloch of a city.

For some reason I was reminded of Paul Klee, had he lived in another century, under the California sun and caved to demands for size. (The Phillips had an informative exhibition on Klee’s lasting influence on other American painters, some years ago.)

Kyle Kilty It could be, Frankly (2022) Acrylic, mica flake and oil on canvas.

Kyle Kilty It Could Get the Railroad (2022) Acrylic, oil, and graphite on canvas

Kyle Kilty Arranging (2019) Acrylic, oil, and gold leaf on canvas

And here, finally, is the essence of story telling about the facets of this city here and now, its hidden treasures and traditions, the diasporic nature of its people due to displacement from their home countries and/or the grid of highways, literally embedded in the substance of L.A. county itself: the soil collected from its various neighborhoods, mixed with salt, rain, limestone and masa. Jackie Amézquita’s 144 slabs are testament to the unwritten history of the many unseen people who constitute the lifeblood of L.A., the embedded drawings representing typical sights during quotidian encounters.

Jackie Amézquita El suelo que nos alimenta (2023) Soil, masa (corn dough), salt, rain, limestone, and copper

Here you can see her at work and hear her explanations of the artwork. It is terrific on so many levels.

***

THERE IS CHANGE AFOOT at the Hammer. This week we learned of the planned retirement of long-time director Ann Philbin, with a search for a replacement underway. It will be difficult to fill those shoes. Hopefully, the core of her focus will endure, a commitment to contemporary art with a focus on emerging artists and social justice. The 2023 biennial certainly can serve as a model: reconsidering the past in the sense that it paves the way for grasping a more equitable future, but then moving on, creating our own utopias.

Started today with an incisive German voice. Might as well end with another one. If you replace the words “(social) revolutions” with “art,” and “19th” with “21st” century, the museum might eventually follow this model:

“The social revolution of the nineteenth century cannot take its poetry from the past but only from the future. It cannot begin with itself before it has stripped away all superstition about the past. The former revolutions required recollections of past world history in order to smother their own content. The revolution of the nineteenth century must let the dead bury their dead in order to arrive at its own content.”

Karl Marx The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. 1852

Mirrored in installation by Guadalupe Rosales.

———————————————

Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living

OCT 1 – DEC 31, 2023

HAMMER MUSEUM

Free for good

10899 Wilshire Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA

90024