Feeling demoralized? Acknowledge it.

Sad? Allow it.

Worried? Accept it.

These emotional reactions have a function, just as positive thinking does. They connect you to others, help you to be alert and prepare you to find protective measures. For a full treatment of emotion regulation, ways in which we manage our feelings if they interfere with daily functioning, I recommend a book by Stanford psychologist James Gross that explores every facet of the process. And since we’re at it, I have also written on the way emotions affect memory, most recently, as of this April, here.

On days when negative feelings approach the level of despair, however, turn to James Baldwin. In his 1964 monograph, Nothing Personal, in response to the Harlem Riots where a Black kid was shot by a White police officer and co-authored with his friend, photographer Richard Avedon who provided portraits, he manages to infuse us with a sense of obligation to live and act and stop despairing. (A detailed review of the edited reprint, (insanely expensive, alas,) here.)

The essay begins with a sly criticism of American advertisement, (sort of ironical when you consider that his collaborator on this book, Avedon, was the most influential fashion photographer of the post-war times) but then turns to the darker issues of being a minority in the United States.

“We have all heard the bit about what a pity it was that Plymouth Rock didn’t land on the Pilgrims instead of the other way around. I have never found this remark very funny. It seems wistful and vindictive to me, containing, furthermore, a very bitter truth. The inertness of that rock meant death for the Indians, enslavement for the blacks, and spiritual disaster for those homeless Europeans who now call themselves Americans and who have never been able to resolve their relationship either to the continent they fled or to the continent they conquered. Leaving aside-as we, mostly, imagine our- selves to be able to do-those people to whom we quaintly refer as minorities, who, without the most tremendous coercion, coercion indistinguishable from despair, would ever have crossed the frightening ocean to come to this desolate place?”

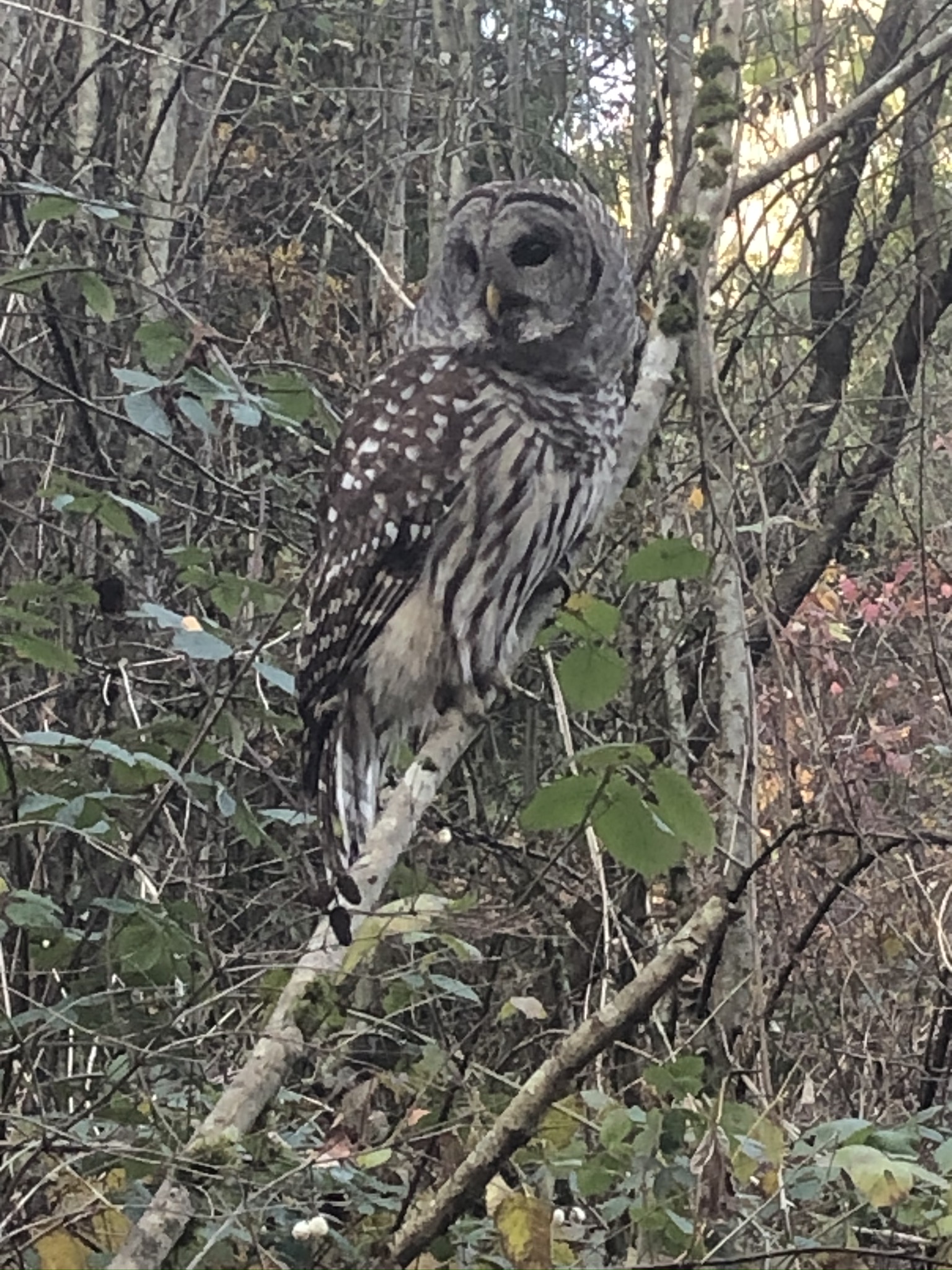

(Photographs today thus of rocks, in grinding sea.)

After describing multiple causes for despair, Baldwin eventually turns to an emphatic call for hope and persistence in dark hours.

“One discovers the light in the darkness, that is what darkness is for; but everything in our lives depends on how we bear the light. It is necessary, while in darkness, to know that there is a light somewhere, to know that in oneself, waiting to be found, there is a light. What the light reveals is danger, and what it demands is faith.”

———

“For nothing is fixed, forever and forever and forever, it is not fixed (emphasis mine;) the earth is always shifting, the light is always changing, the sea does not cease to grind down rock. Generations do not cease to be born, and we are responsible to them because we are the only witnesses they have.

The sea rises, the light fails, lovers cling to each other, and children cling to us. The moment we cease to hold each other, the moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us and the light goes out.”

Full text of the essay (print it and keep it on your night stand for dark hours!) here.

We might not be able to hold each other physically right now, but the idea is of course at its root one of mutual support and reciprocal solidarity with each other. We can be the light for others, even in hours where things get pretty dark within our own soul. Be a light for someone else, it’ll reflect back, I’ll guarantee it, just as I concur with the claim that nothing is fixed. Ever. We simply need to adjust our time horizons.

Smith’s lyrics for Long Old Road are cited in the essay. Here is the music.

LONG OLD ROAD Bessie Smith 1931 Bessie Smith rec June 11th 1931 New York

It’s a long old road, but I’m gonna find the end, It’s a long old road, but I’m gonna find the end, And when I get there, I’m gonna shake hands with a friend.

On the side of the road,I sat underneath a tree, On the side of the road,I sat underneath a tree, Nobody knows a thought that came over me.

Weepin’ and cryin’, tears fallin’on the ground, Weepin’ and cryin’, tears fallin’on the ground, When I got to the end, I was so worried down.

Picked up my bag, baby, and I tried again, Picked up my bag, baby, and I tried again, I got to make it, I’ve got to find the end!

You can’t trust nobody, you might as well be alone, You can’t trust nobody, you might as well be alone, Found my long lost friend, and I might as well stayed at home!

And here is a full album.