When I was young and impressionable I had to read a book titled Hunger by Knut Hamsun. Why they would serve us literary fare by a Norwegian Nazi remains a mystery. Maybe my German high school teacher was as enamored by the Nobel Prize author as were many others, more famous people: Maxim Gorky, Thomas Mann, and Isaac Bashevis Singer. The book explores the psychological decline of a pretty asocial character who is driven almost mad by hunger, but as a consequence of refusing available food, fully in line with Hamsun’s celebration of individualism and freedom to choose. In the end the protagonist escapes his woes by hiring on to a ship and sail the seas, being fed, presumably, three meals a day. It felt odd, even to a 15-year old, that hunger was not presented as an inescapable scourge for the many who lack access to food, but as a choice. Some of my thoughts on the issue of food insecurity you’ve read in earlier blogs.

Decades later, I came across this:

Hunger Camp at Jaslo

Write it. Write. In ordinary ink

on ordinary paper: they were given no food,

they all died of hunger. “All. How many?

It’s a big meadow. How much grass

for each one?” Write: I don’t know.

History counts its skeletons in round numbers.

A thousand and one remains a thousand,

as though the one had never existed:

an imaginary embryo, an empty cradle,

an ABC never read,

air that laughs, cries, grows,

emptiness running down steps toward the garden,

nobody’s place in the line.

We stand in the meadow where it became flesh,

and the meadow is silent as a false witness.

Sunny. Green. Nearby, a forest

with wood for chewing and water under the bark-

every day a full ration of the view

until you go blind. Overhead, a bird-

the shadow of its life-giving wings

brushed their lips. Their jaws opened.

Teeth clacked against teeth.

At night, the sickle moon shone in the sky

and reaped wheat for their bread.

Hands came floating from blackened icons,

empty cups in their fingers.

On a spit of barbed wire,

a man was turning.

They sang with their mouths full of earth.

“A lovely song of how war strikes straight

at the heart.” Write: how silent.

“Yes.”

Translated by Grazyna Drabik and Austin Flint

I know, it’s the week of Christmas. Visions of food associated with the occasion, pungent smells permeating houses, meals shared with loved ones, unusual things like goose or carp (if you are German,) gingerbread and Stollen (a baked Marzipani concoction of about a million calories per slice,) all mouthwatering and sweet. Now why do I have to ruin that by reminding us of hunger as a weapon, an instrument of torture, a tool of extermination? Yes, a whole region of Jews were killed by being driven into a corral near the town of Jaslo and refused food and water. Can’t we let the past rest, at least during this week of celebration?

I would, if it were only the past. Just as Szymborska exhorts us to keep the memory alive – Write it. Write. – I cannot but say it, say: we are faced with hunger by design, here and now, in our American Prison system. There a few who bear witness. Last week this singular report was published by the ACLU of Southern California in cooperation with various other organizations. It “combines testimonies from people who were incarcerated in the Orange County jails during the pandemic with public records. Nutrition facts, menu items, and budget information gathered from the Orange County Sheriff’s Department through Public Records Act request.”

For almost two years now the thousands of inmates in this system have not had a hot meal. The three meals they get are mostly inedible sack lunches that contain moldy bread, spoiled slices of meat, and an occasional apple or orange. It is not enough food, particularly if you cannot eat it if it’s rotting, and it is so unhealthy that food-related illnesses have skyrocketed. Food poisoning from the spoiled food is one thing; the high sodium and carbohydrate contents have increased heart disease, diabetes-related problems, and circulatory system illness.

The situation has gotten so bad, that even the Board of State and Community Corrections asked the jails to add hot meals after their inspection revealed the horror of the situation. What happened? Hot cereal was added to breakfast, but soon after refused again. Soup was added to dinner (high-sodium broth with floating onion and tomatoes to be found with a magnifying glass.) However, the soup was put on the floor in front of the cells, often only accessible after an hour when it had become cold and by now detected by bugs that live in the shadows of the prison hallways, equally desperate to improve their food intake.

Kitchen closures where justified with Covid-19. The closures saved a good amount of money to the prison system, none of which has been re-invested into better nutrition for the inmates. In addition, the system has made a significant amount of revenue on items that incarcerated people can purchase through commissary (some $10.000.000 a year.) That kind of food might be more edible than bug-infested soup, but it is also not healthy, like most items that come out of dispenser. Medical and religious diets have been denied due to Covid restrictions, or so it is claimed.

“If a budget recipient spends less than its predicted budget, the surplus rolls over or goes towards other department expenses. That means that when OCSD receives a budget for food services and ultimately spends less than was budgeted, the remainder rolls over and can be used for other expenses like staff salaries. That is what happened when OCSD shut down the hot kitchens.”

These are the numbers that show the development during the Covid years, all on the backs of the inmates.

I”n 2018, OCSD rolled over just $72,000 from the food budget to use on other OCSD expenses; in 2019, OCSD rolled over $90,000. In 2020, after OCSD stopped serving hot food, they rolled over $963,013. In 2021, OCSD is on track to rollover $656,472.”

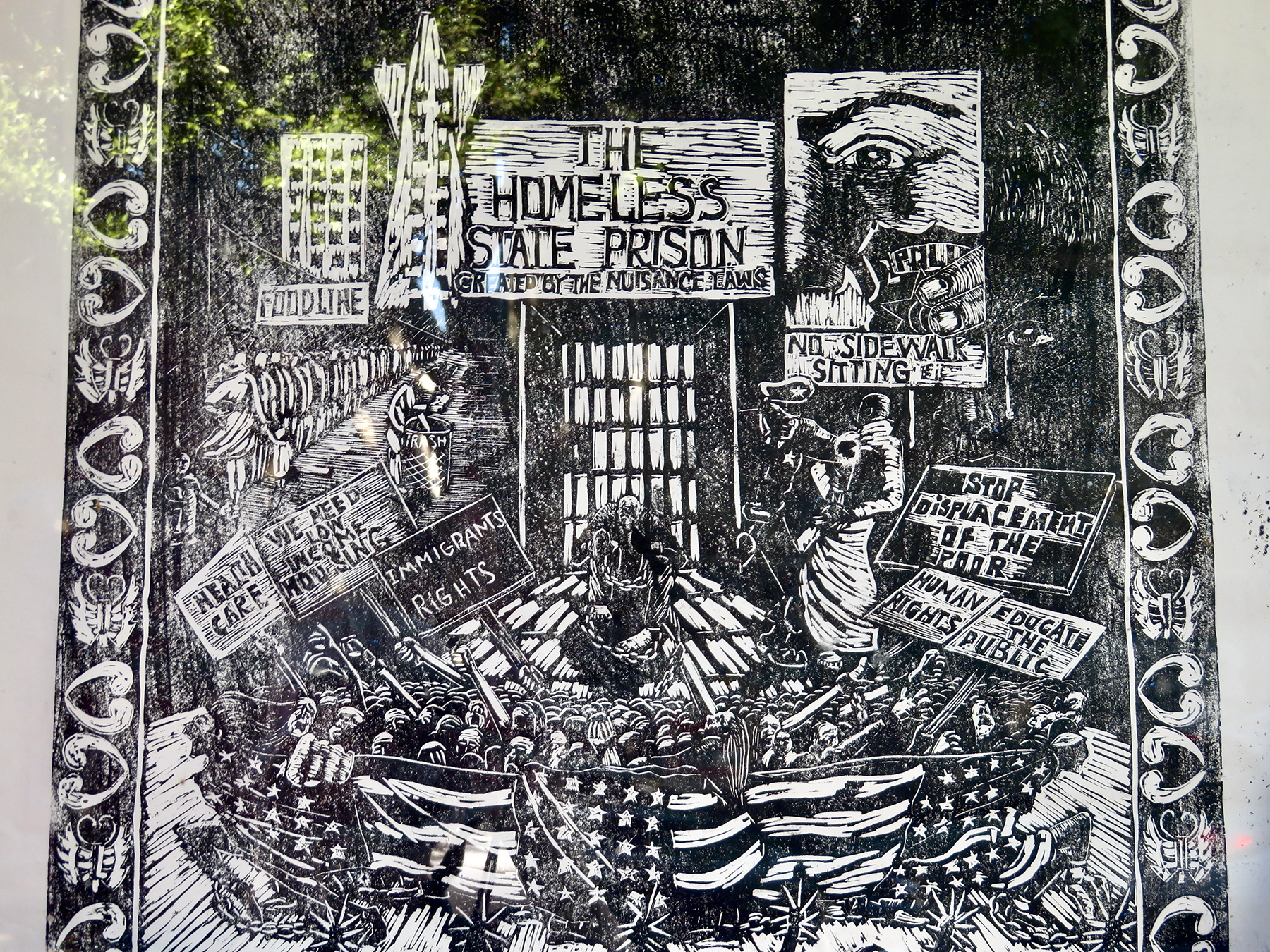

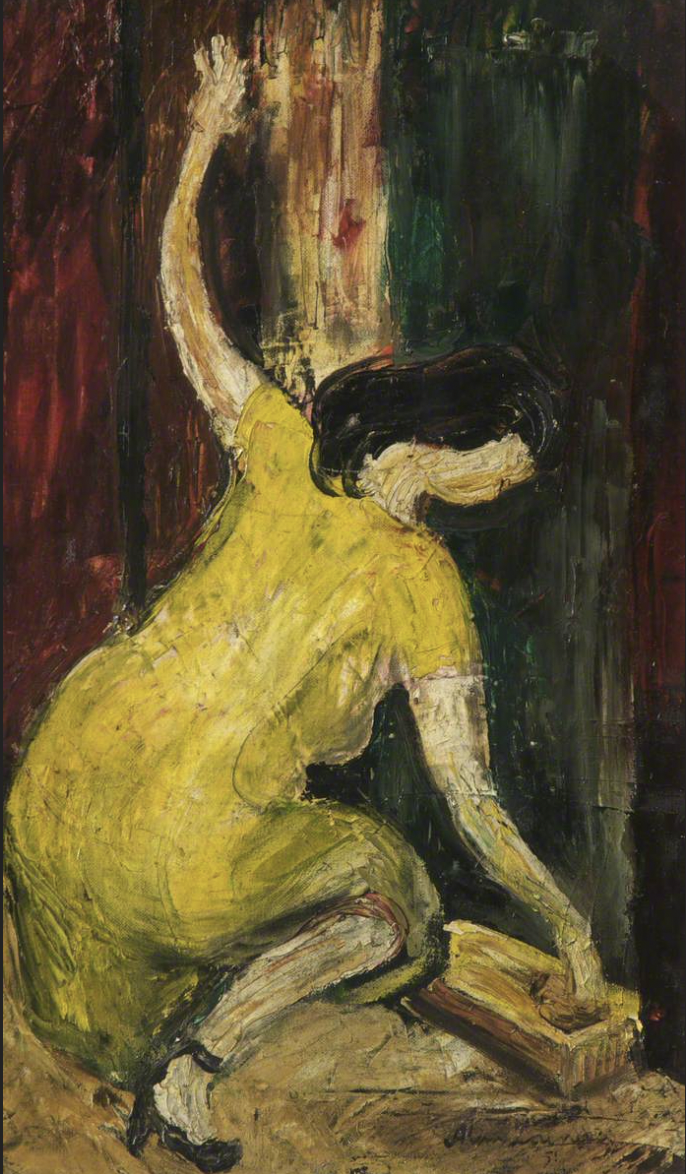

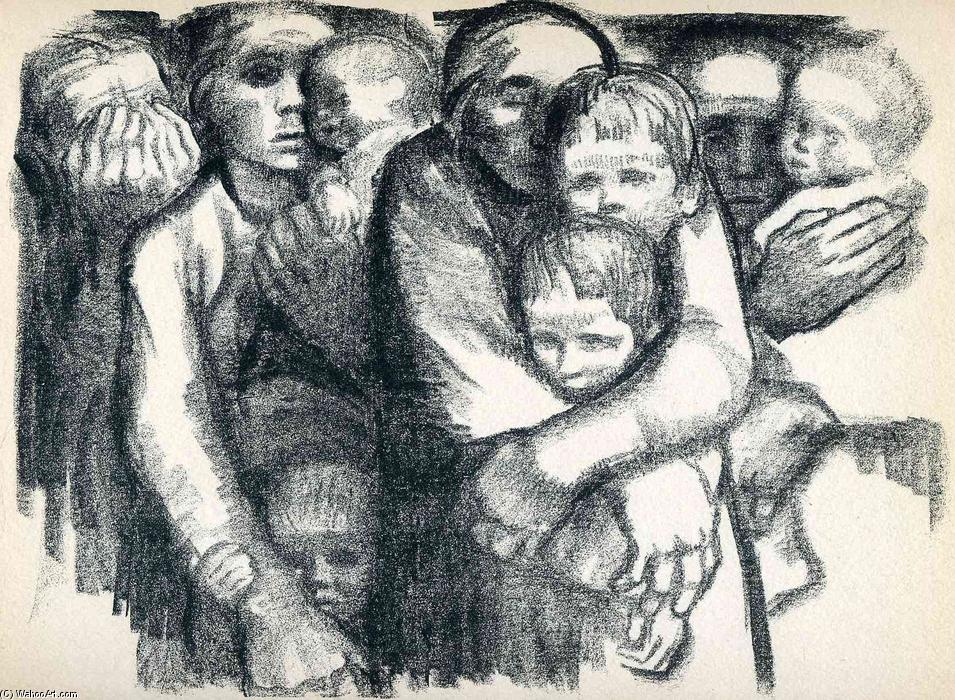

You can find all the details and art work and experiential testimony by the inmates in the report. Images today were created by the prisoners.

I do not know if the situation is any different in Oregon. But I do feel that we are ignorant of all of it unless we happen to have our noses pushed into it. Without knowing, of course, there will be no memory, no transmission of the horrors of one’s times to future generations as a warning. And poets will have to dig up a past that we failed to change in our present. Spread the word, if you can. The link to the report, again, is here.

Music by Bob Marley.