TO PUT IT BLUNTLY: I came for the art. Stayed for the history. And left with a mind filled with thoughts about access to education. It all started out, however, with standing at the doorstep of the wrong museum.

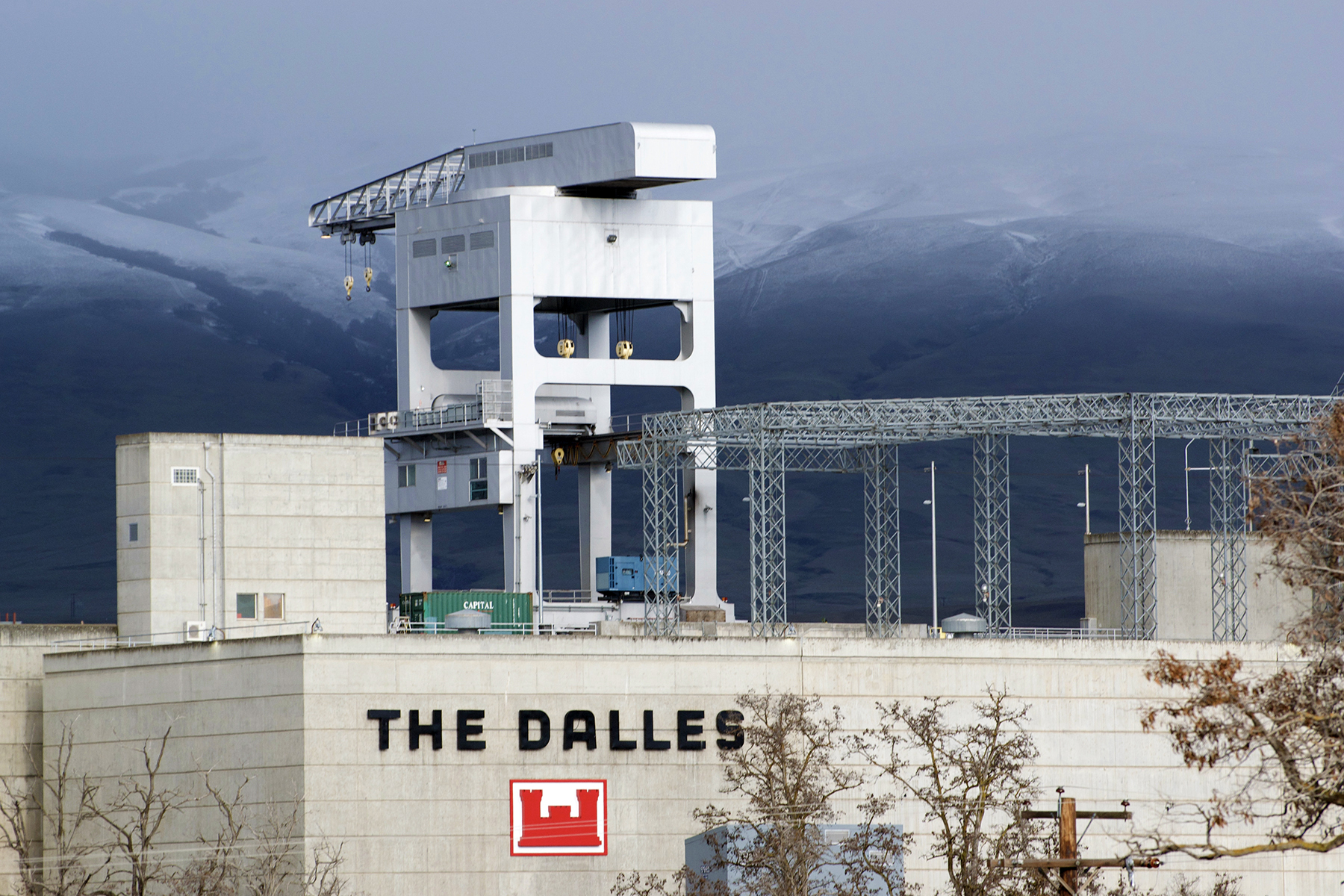

Leave it to me and my heat-addled brain to drive to Newport, OR to visit OSU’s current Art About Agriculture exhibit displayed at a Lincoln County Historical Society‘s venue, look up the address for something called “museum” and end up at the Society’s Burrows House. Which was closed. I rang the doorbell and a startled, but exceedingly friendly book keeper tried to figure out who I was and what I wanted. Ah, I was supposed to be at the Pacific Maritime Heritage Center (PMHC) overlooking the bay and the iconic Yaquina Bay bridge!

Good thing that my ridiculously stereotypical German punctuality had left some leeway to make it in time to the appointed meetings across town with the various parties involved in my query to learn more about what’s going on in Newport, OR. Somewhat flustered, nonetheless. Soon absorbed by so much I had to take in.

Let us first look at The Sustainable Feast (August 5- September 30, 2022) a collection of artworks about food production and consumption. It was in the process of being hung by Owen Premore, Directing Curator of OSU’s College of Agricultural Sciences, when I arrived. Curating so many diverse works across two locations (the Visual Art Center at Nye Beach is the second one) is an art in itself – the sequencing as demanding as the mounting. Premore had his work cut out for him, while also training museum staff how to hang and distribute. Consider the statistics:

Number of art submissions to the open call: 290 artworks by 91 artists. Counties represented: 12 Oregon counties, 5 Washington counties, and Kaua’I County in Hawai’i. Artworks selected for inclusion in the tour by a blind jury: 59 artworks by 47 artists. Artworks at PMHC: 49 artworks by 47 artists. Artworks at VAC: 12 artworks by 12 artists

Quite a feat.

I will then turn to what I learned about the Maritime Center and its new Executive Director, Susan M.G. Tissot, appointed at the beginning of May, who gave me the grand tour of the building, related its history and provided much food for thought. Finally I will fill you in with what’s new at Newport’s Visual Arts Center, which is also exhibiting some of the Sustainable Feast‘s displays in the Upstairs Gallery (August 5 to 28, 2022) and has new leadership as well. Yes, it was a full day. Glorious, too.

***

FOR ALMOST 40 YEARS, OSU’s College of Agricultural Science has called on local artists to submit work that helps bring people closer to agricultural resources and research, increasing our understanding and valuing of agriculture, diversity of approaches and innovation in our food system. At its core it is an educational mission, one made possible by significant resources put into the Art in Ag production, including helping the annual show tour across the state for maximal access for visitors. Included is the acquisition of jury-selected art works for the University’s Permanent Collection, which at this time holds fiber arts, mixed media assemblages, paintings, sculptures, watercolors, and works on paper including drawings, photographs, and prints. Permanent collection displays can be found across the state, including at the OSU campus in Corvallis, the Oregon Housing and Community Services in Salem, and the Oregon Food Bank and Wheat Marketing Center in Portland.

The current exhibition shows a wide array of media, and ranges from mediocre to stellar exhibits, a fact I found particularly appealing: this is not an elitist display, but a cross section of artists of all levels interacting with nature, their eco systems, the way food is processed and problems or successes associated with issues related to agriculture. Rather than being in awe, the visitor is drawn in, recognizing our own place and time, exposed to art that is quietly accessible.

I am featuring below selected works that give an impression of the range of media and topics. Go visit the exhibition to get the full sense of artistic talent!

Toni Avery Grey Skies, Golden Fields Acrylic

As a photographer I was of course drawn to particularly strong work by Loren Nelson, David Schaerer, and someone new to me, Craig J. Barber. Whether you depict the simple beauty of a vegetable,

Loren Nelson Bent Pepper, 1999 Black&White Photograph, Archival Pigment Print

or the interaction with the land,

Dave Schaerer Commercial Clam Diggers 2 2012

Digital photographic print

often made harsh by working conditions under a system that has not been kind to or even exploitative and harmful to those it hires, the photographs engage the viewer to think through the issues. This is particularly relevant in a year where farm workers in Oregon, most of them Latinos, have finally been granted overtime pay, something they had been excluded from since the federal 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act. Since June and July, Oregon also has new OSHA state rules that protect workers when temperatures soar beyond 80 degree or the air becomes clogged with wildfire smoke.

Craig J. Barber Trimming Rhubarb

Photography: archival pigment inks on fine art rag paper

The heat protections require employers to allow workers to take paid breaks to get relief from the heat, provide access to shade areas outdoors and an adequate supply of drinking water, have a heat illness prevention plan and to gradually introduce workers to high temperatures. Some 87.000 farm workers, independent of immigration status, construction workers, forestry professionals, highway workers, and utility personnel will be protected. (Ref.)

Craig J. Barber Hooking Up an Irrigation Hose

Photography: archival pigment inks on fine art rag paper

My eye was caught by a mixed media exhibit by a local Newport artist that teemed with detail, helping us understand the biodiversity required for healthy soil.

Carol Shenk Healthy Soil Biodiversity

Mixed media – Details below

My interest was piqued by a mixed media installation that informed, in rebus-like fashion, about animal husbandry and intergenerational transfer of knowledge on a Central Oregon sheep farm in Crook County.

Andries Fourie Powell Butte Romneys Mixed media

There was fiber art,

Sheryl LeBlanc Eat Uni and Help the Kelp Fiber arts

unusual bead work,

A. Kimberlin Blackburn A Farmer’s Life with Luna at the Waterfall 2022 Glass beads, acrylic, thread and up-cycled ceramics

gorgeous sculpture of fungi,

Hsin-Yi Huang The Magnificent Fungi 2022 Porcelain fired to Cone 8 in oxidation atmosphere

and a cabbage.

Crista Ames Unfurl

Ceramic: stoneware

There was whimsical work combining installation and photography (all the vegetables were photographed at markets by the artist.)

James Erickson Singer Farms Mixed media sculpture

Video installation could be found next to traditional paintings.

Katy Cauker Orchard Late Summer – Carpenter Hill 2022 Acrylic on Canvas

Julia Bradshaw Cafeteria 2022 – Video, Chafing Dish, TV Monitor – you saw empty dishes moving along an assembly line inside the chafing dish, clever.

Mabel Astarloa Haley Decay 2 2022 Oil

***

THE EXHIBITION AT THE MARITIME CENTER is located in the Mezzanine, a space recently refinished, plied with soft carpeting to shelter from uneven floor planks, equipped with beautiful exhibition panels, and with a professional lighting system that tells you right off the bat that Susan Tissot is not a woman of half measures. If something needs done, it will get done right.

30 years of experience in the museum world, including 19 years as Executive Director at different institutions across the western states and Hawai’i, have produced an accumulated knowledge base and varied skill set (think fundraising, grant writing, and above all museum development) that are surely needed in the current situation: cultural institutions all over the place have been battled by economic factors, the closures and difficult working conditions due to the pandemic, with non-profits some of the hardest hit.

What stood out to me in our interaction, though, was Tissot’s infectious enthusiasm for education and her curiosity in conversation. Here was a woman who could have simply made a sales pitch to get her institution on the map – plenty of positive features to highlight, intriguing history of the building to report, neat stuff to show. All of which she did, mind you – I now know the history of a house built by wealthy entrepreneurs, converted into nightclubs and restaurants, and eventual transformation of this beautiful space with its breathtaking views into the current historical center.

The Doerfler Family Theater, for example, is in the building’s basement. There you can directly choose which of 12 short documentaries you would like to see. It also serves as an auditorium for a variety of performances and belongs on a long list of things that hold much potential for this venue. The varied engagement of community members is formidable. To mention just a few, the Board President and retired Director of the Port of Toledo, Bud Schoemake, spent the last 18 years working tirelessly on the building and also oversaw project management of the mezzanine remodel.

Jo An McAdams, the Board Secretary has also been very involved; she is a USCG wife whose husband was a Master Chief. Jo An got the USCG in Newport to help the PMHC do some heavy lifting getting the new exhibit panels here and up on the mezzanine from the shop in Toledo. Joe Novello, a retired US Coast Guard, educator and author who runs the Toledo Community BoatHouse worked with Schoemake on the exhibit panels. Art exhibits are lined up for the near future that will speak to a variety of interests and regional strengths.

But Tissot became truly passionate when we started to talk about education in the context of another current exhibit, Animals in Nature/Art & Artifacts: “from the forest, air and sea.” in the main floor Galley Gallery (July 21 – October 9, 2022.)

The work of three Northwest artists, Cascade Head artist Duncan Berry’s Gyotaku printing on wood panels, McMinnville artist Andy Kerr’s wildlife painting on wood panels and Lincoln City artist Nora Sherwood’s bird illustrations on paper are pretty striking.

The visual art is paired with objects from the museum’s collection, taxidermy specimens including exquisite maritime birds, and a hands-on opportunity that includes wildlife pelts for kids of all ages, courtesy of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Tissot very much wants to provide occasions for the general public, children included, that allow people not just to experience wonder or surprise, but that makes them ask questions, the very first step to become more engaged, be it in science or art.

Not the easiest thing to do, when your institution runs on a staff of 5, and is physically slightly removed from the tourist strip that is Bay Boulevard in Newports’ Historic district, if only by a few steps up a staircase, or a driveway that leads to plenty of free parking behind the building. That distance is enough to have people blindly walk by, not aware of what one misses. I, too, plead guilty of not even knowing about the PMHC, despite annual pilgrimages to Newport with the kids, who would have just loved, loved, loved this museum. (Here, by the way, is an online resource for maritime institutions nationally that you can visit, virtually in may cases. Use it as a teaser and then explore the real thing in Newport!)

Andy Kerr Owl Painting on Wood

Here is an interview where Tissot explains the plan for public programs. Still to come are a free Exhibit Art Talk on August 21, 1-3 pm about how nature is used as inspiration for art with artists Duncan Berry and Nora Sherwood. They also discuss the reasons why they focus on the subject. And on Sunday August 28, 1pm, Skyler Gerrity, Assistant District Wildlife Biologist, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, will be at the PMHC to give a presentation on How to live peacefully with our local black bears.

***

I RECENTLY LISTENED TO AN INTERVIEW with Heidi Zuckerman a young American leader in contemporary art, formerly a curator at the Jewish Museum in New York City and the Berkeley Art Museum. As CEO and Director of OCMA/The Orange County Museum of Art in California, she is building a new, ground-up project with Pritzker Architecture Prize winner Thom Mayne, as well as producing podcasts featuring conversations about art. She talked about her three criteria for a successful institution that serves the public (other than free access which is only a possibility if you have a wealthy and generous donor base. One should be so lucky.) She listed:

1) looking back to look forward – have history as a guide.

2) be mindful of place – anchor yourself locally and within the specifics of your time (awareness of what Covid has done to us and institutions was one example she used.)

3) caring and sharing – be aware of the needs of the community you want to reach, and approach them, invite them, engage them where they are, rather than expecting them to find their way to you.

I was thinking that Tissot’s approach to her work – and partially what PMHC has done since its inception – really fits with these criteria, biding well for the institution. History is preserved, explored, taught; it is anchored in place, focussing on local needs, interests and struggles. (One of her biggest achievements, in her own words, for example, was support for an oral history program (Center for Oral History, Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawai’i at Manoa) that taught younger generations of Hawai’ians about the devastation and horrors of previous tsunamis destroying the islands.) And she is a conversational partner, caring and sharing indeed, not just a representative of an institution, but voicing interest in her interviewer and taking time to discuss shared concerns about how art can be of help in education. She was clearly curious about who she interacted with, something that happens rarely in my reporting experience.

Let’s help keep the PMHC afloat!

***

THE NEWPORT Visual Arts Center, my last stop for that day, has seen its share of challenges as well. After admiring the Sustainable Feast artworks displayed in the Upper Gallery (selective images are posted below,) I was sitting down with Sara Siggelkow, OCCA Arts Education Manager, well known for her important role in Newport’s paper book arts festival, and OCCA Executive Director Jason Holland, who arrived in 2020 after 18 years of experience in various roles at Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa, California.

The Covid pandemic had a huge impact on the institution given that educational classes and camps could not take place, and performances at the Performing Arts Center had to be canceled. At this point the institution operates with 50% of the original staff, a large decrease for an organization and a major upheaval for those who lost their jobs, some permanently, in a small community where the arts are likely not hiring for some time to come. Lay-offs are always difficult, but particularly jarring when alternative options are slim.

Holland emphasized how much flexibility is needed and day-to-day decision making required to adapt to new and ever changing circumstances. He was excited to be joined in this venture by a new Director of the Visual Arts Center. Ceramic artist Chasse Davidson who operated Toledo Clayworks from 2015 thru 2020, served as Toledo Arts Guild President 2014-2015, and has participated in the Newport Visual Art Center’s Steering Committee since 2020, will join the staff.

Robin Host Crab Season 2022 Acrylic and Paper Collage on Panel

Bill Marshall Quamash 2022 Watercolor

Lisa Brinkman Sophia’s Garden 2022 Eco-prints of sumac, eucalyptus, and maple, cold wax and oils on raw

silk canvas

I was fully familiar with the important role the VAC plays for Oregonian artists as a place to exhibit art. I knew much less about its role in education, beyond my general knowledge of summer camps and year-round classes. Both Holland and Siggelkow reported on their venture with the Oregon Coast Art Bus, a vehicle that literally brings art to the people, instead of people to the arts center. Or, to be more precise, brings the chance of making art and thus involvement in art to those who might be stuck in their communities due to lack of transportation, funding, or simply information.

Oregon Coast Council for the Arts is pleased to announce the creation of a new mobile arts-learning platform—The Oregon Coast Art Bus, which will bring creative learning projects to students throughout Lincoln County this summer and beyond. The project has been funded by the K-12 Summer Learning Fund of the Oregon Community Foundation and is designed to address the “opportunity gap” associated with educational challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Oregon Coast Art Bus’s summer initiative will focus on under-served youth populations. The Bus event will be free and families are encouraged attend.

The bus comes equipped with an arsenal of tools to introduce a theme, parks at the local library, or a box store parking lot, or a sports field, and everyone can come and participate. For the last round it was printing of nature’s bounty. Planned for the next round are geometric shapes. Struck me as a splendid idea, and I wonder how many counties in Oregon could copy that approach to help children find access to and grow an interest in art. Here is a detailed article on the project published in Oregon Arts Watch last year.

Looking forward, concerned with place and sharing and caring here as well. Art is in good hands at the Oregon coast. A sustainable feast with our continued support.

Artwork by a child participating in the activities offered by the Art Bus crew.

And finally a note to my regular readers: I will take the rest of the month off, an earned break!, see you in September.