Last week I came across a short interview with some notable writers all focused on the climate crisis. Rebecca Solnit, Thelma Young Lutunatabua, James Miller and Jay Griffiths were asked multiple questions concerning their own relationship to the crisis, their levels of engagement, their hopes and fears. When asked about the efficacy of the written word for a fight against the climate crisis, their responses ranged from hope and enthusiasm to doubt. One answer lingered with me: “I embrace all forms of storytelling, and I think all are necessary in this struggle. We have to tap into people’s imaginations and show them that another world is possible.”

That is of course one of the many functions of art, showing possible worlds, next to creating beauty, communicating ideas, raising consciousness, being the canary in the coal mine. I want to focus today on how photography can serve as a window into a different, private world that allows us to see people who are perhaps different from ourselves and yet utterly familiar in their mundane settings, poses, and demeanors. With that it creates the possibility of empathy if not bonding, in a way that writing about the subject never would (at least not immediately), words relying on facts and persuasion, rather than the direct emotional involvement created by the narrative of imagery.

The photographs, a century apart, depict queer folk, and I want to stress that today’s musings are not about the issue of transgender origins, medical procedures for transitioning, or transphobia, although all warrant close examination in an era that has made the topic into a tribal rallying cry for exclusion and worse. The intensity of the debate echos other preoccupations with the “order” of things, the retention of existing hierarchies or the need for simple binary truths in this world, an either/or thinking that avoids engagement with choice and uncertainties. (And of course a backlash against the enormous progress made in the area of sexual orientation, including the right to marry a same-sex partner.)

That said, here are the biological facts. Biological categories do exist – have some objective reality in the sense that if, for example, your genetics have an xy pattern, it is enormously likely that you have an anatomy associated with males and a biochemistry associated with males, and if you are biologically xx, the same applies for women. But that reality sits alongside of the undeniable fact that there is a substantial number of people who don’t fit this pattern. Biologically some have traits that are strongly associated with male and female. And in still other cases they have biological traits that are neither typically male nor typically female, and so for example their genetic pattern is entirely different, having xo or xxy chromosomes. One more step: if this is undeniably true at the level of biology, it would be astonishing if it wasn’t reflected in people’s psychology, with one example of many, some people feeling they were born into the wrong body, and often having these feelings from a very young age.

But again, what I am after today, is how photography, in the depiction of something or someone who is different, can create a sense of familiarity nonetheless, and can convey a shared humanity. It does so by offering a narrative that invites the viewer into daily routine, anything other than the exotic fantasies contained in the stereotypes held by those feeling disgusted, alienated or threatened by queerness.

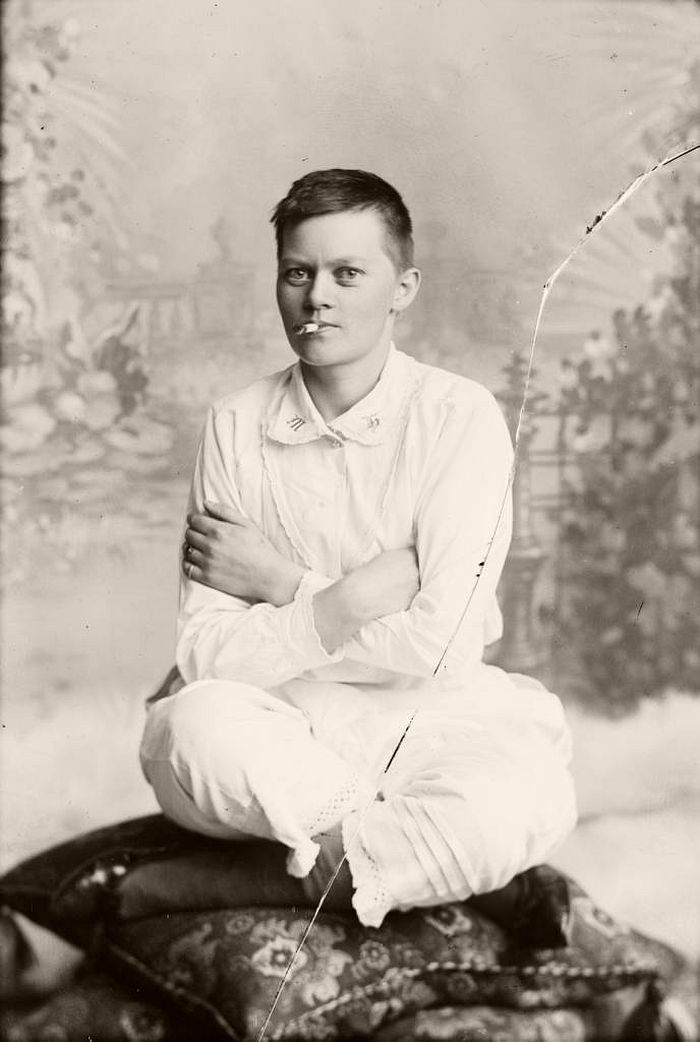

The first selection is the work of two Scandinavian women photographers, Marie Høeg (1866 – 1949) and Bolette Berg (1872 -1944), who met in Finland and lived in Norway, as business partners and as a couple. They were suffragettes and quite engaged in feminist politics on the local level, while making a living by conventional photography, studio portraits and the like. Høeg founded the Horten Branch of the National Association for Women’s Suffrage, the Horten Women’s Council and the Horten Tuberculosis Association. Berg worked more behind the camera. The photographs were part of some 400 glass plates found in a barn of their farm decades after they had died. Marked “private,” they contained images that played with gender roles, cross dressing, mimicking behavior reserved for men (arctic explorers in fur coats,) showing the androgynous protagonist as well as a number of their friends joyously defying gender norms.

The work has a home at Norway’s national photography museum, the Preus Museum in Horten. It is currently shown at the ongoing Festival of Photography and Visual Arts, PHotoEspaña, in Madrid until September.

As you can see, the couple poses like a traditional heterosexual couple at home, going out in the boat (or sitting for a photographer in these studio props that were known to anyone at the time,) interacting with their pet, and having fun at drinking, smoking and playing cards with friends (behavior reserved for men at the time) independent of gender.

A few of the photographs show a male friend not averse to cross-dressing.

Fast forward to 120 years later, and a different part of the world. Camila Falcão has been photographing Brazilian trans women (women born into male bodies), encouraging them to pose as they wish, in their own environments. (All photographs are from her website.) Brazil’s 2019 law that considers transphobia a crime has done nothing to lower the murder rate of Brazilian queer people: it is the highest in the world, for the 13th consecutive year, with a 30% rate of 4000 killings in that span of time.

The title of Falcão’s series, “Abaixa que é tiro” refers to the reactions of the portrayed and their friends, who started commenting ‘Abaixa que é tiro!’, celebrating being shown to the world. “The expression is used widely among the Brazilian LGBT community to address that something really awesome/fabulous is about to hit you. More in general, however, it could be said that “Abaixa que é tiro” signals a paradoxical relationship between fear and empowerment.” (Ref.)

Again, notice how an attachment to pets immediately confers familiarity.

Women are tired, women break arms, women have friends.

Women are barely out of childhood,

could be on a winning gymnastics team,

a first grade teacher,

or the smart, uncompromising sister who sets you right.

Work like this can help to deconstruct stereotypes, although it will be a long road until increased visibility leads to a decrease in violence against this population. The photography world is noticing. We have now venerable institutions calling for work to show what unites us in times of division, like, for example, the British Journal of Photography, having judged exhibitions of Portraits of Humanity. Every single image that manages to shift our consciousness and beliefs is worth it, even if not all of us can have Falcão’s talent, access or courage as an ally to a demonized minority.

Music today is sung in Portuguese by Joao de Sousa, but created by a Polish collective, Bastarda, that has the most amazing modern Jewish music in their repertoire. Check them out. I have been listening to Fado non stop for weeks.