What would you say are the most important tools harnessed by early mankind? Fire? The Wheel? Agriculture? Does string even come to mind?

It did not, for me, until I embarked on a bit of reading about the history of string after I was stupefied by an archeological find that dates some 35.000 years back, a tool that allowed a small group of people working together to produce meters and meters of strong rope in about 10 minutes.

Single threads are not particularly useful. Twist them into yarn, though, or make yarn into strands, or strands into string and then ropes, and you have something that powerfully affects your interactions with the world. Our idioms tell the tale: learn the ropes, spin a yarn, hang by a thread, tie the knot, thread the needle, string along, cut the cord, moral fibre, loose the thread – where was I?

“A string can cut, choke, and trip; it can also link, bandage, and reel. String makes it possible to sew, to shoot an arrow, to strum a chord. It’s difficult to think of an aspect of human culture that is not laced through with some form of string or rope; it has helped us develop shelter, clothing, agriculture, weaponry, art, mathematics, and oral hygiene. Without string, our ancestors could not have domesticated horses and cattle or efficiently plowed the earth to grow crops. If not for rope, the great stone monuments of the world—Stonehenge, the Pyramids at Giza, the moai of Easter Island—would still be recumbent. In a fiberless world, the age of naval exploration would never have happened; early light bulbs would have lacked suitable filaments; the pendulum would never have inspired advances in physics and timekeeping.” (Ref.)

We lace our shoes with string, we get sewn up on the operating table with string, our clothes are woven from twisted fibers, and much of what is tied in knots depends on cordage. Hunting or camping involves plenty of ropes. String has been used as a form of mathematical expression by indigenous people in South America thousands of years ago. A system of knots and tassels hanging from a central strand would record census data and tax information. The language of modern technology refers to strings and threads as well – string theory, web-sites, links, Threads (e.g. the replacement site harboring all of us fleeing from formerly known as Twitter.)

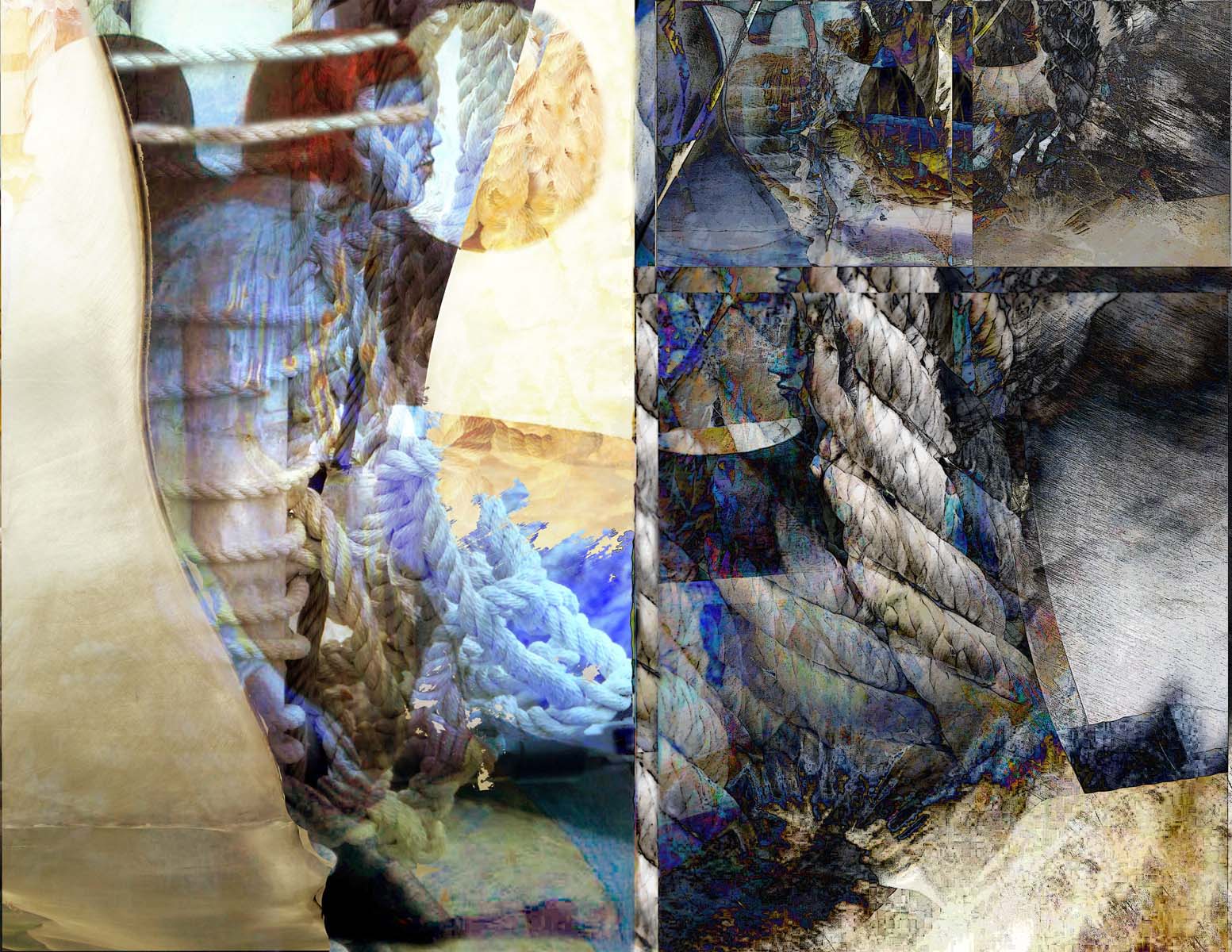

One of the biggest and most consequential uses of string were, of course, the ropes and woven sails that enabled naval exploration: centuries of warfare, colonialism, but also economic trade and scientific exploration depended on cordage that made those boats functional. It was not just the rigging of sails. You also need rope to tow ships, and, to this day, tie even modern ships in harbor. You need hoist cables for cranes, winches, and dumbwaiters as well as woven fenders.

The history books tied rope making to early inventions and practices in Egypt, between 2000 and 1750 BCE. But archeologists knew of much earlier use by indigenous people of ready-made threads, like grasses, vines and pliable roots. Eventually people discovered that you can twist the fibers extracted from plants and animals into ropes, with pliable plants like agave, coconut, cotton, willow, and pond reeds producing strong fibers.

Here is the finding that blew my mind: archeologists unearthed tools made in the Paleolithic, some 35.000 – 40.000 years ago, that were used to manufacture rope. Excavated from a cave in southwest Germany, these are ivory batons, about 8 inches long, that have four holes containing 6 precisely carved, sharp spiral grooves.

The scientists experimented with replicas of the tools (called a Lochstab in German) to see what could possibly be processed with them.

“Individual holes of the Lochstab did not prove effective for pretreating sinew, flax, nettles, and hemp, but we achieved positive results for cattail, linden, and willow. Cattail was particularly applicable because the Lochstab could help to remove the starch for consumption by crushing the outer harder surface of the stems while separating the fibers for cordage. The use of cattail for making rope is well documented ethnographically, and archaeological accounts exist, in particular for later periods. Cattail is highly useful for food, cordage, and basketry.

The tool’s relevance lies in making thicker, stronger rope consisting of two to four strands. We twisted and fed bundles of cattail leaves through the holes. The holes help to maintain a regular thickness of the strands and facilitate the addition of new material necessary for making long stretches of rope. The grooves help to break down the leaves and orient the fibers while maintaining the torsion needed for rope making. The four-holed tool is then pulled with regular speed over the strands . Behind the tool, the strands combine automatically into a rope as a result of their twisting tension. The number of holes used determines the thickness of the rope. Because one person is needed to twist and maintain tension on each of the strands and one to operate the Lochstab, three to five people would be needed to use a four-holed Lochstab for rope making. Our experiments using cattail and four or five participants typically produced 5 m of strong and supple rope in 10 min.”

What fascinates me is not just that they figured out this tool per se. Using it also required social cooperation, communication and shared goals, bonding the people to each other and thus gaining an advantage over groups that had less developed technology and reciprocal labor. Shared labor led to in-group cohesion, augmenting survival. 35.000 years ago!

Here are some musical references to skipping rope – a childhood activity I preferred much over tug-of-war, wouldn’t you know it. There is Ukrainian composer Viktor Kosenko‘s 24 Children pieces that include jumping rope, Khatchaturian‘s Skipping rope, there is the Children’s Suite Op. 9 by Ding-Shande, really a sweet piece also referring to jumprope, and a piece for harp by Carlos Salzedo that includes Skipping Rope.